In spite of describing an important set of social and economic transformations, the word financialization has become used so frequently and in so many contradictory ways, that it risks becoming as fragile and confusing as other recent buzz-words like globalization, neoliberalism and gentrification. Yet the forces at work behind the term are real and have far reaching impact on citizens, cities, theorists and activists; and we ignore it at our peril.

I define financialization as the growing power and influence of the finance capital, one particularly important and unique branch of the capitalist economy. But while most critics and commentators imagine financialization as a purely economic affair, I see it at work across and between the fields of economics, politics, society and culture. I think it is absolutely crucial to see how these forms work together if we are to understand and confront financialization.

Economically speaking, financialization refers first and foremost to the increased size and power of the financial service industry, sometimes called the FIRE (Finance, Insurance and Real Estate) sector of the economy. Over the past 40 years the FIRE sector has grown to become the single largest economic engine in many economies and in many global cities. This growth has taken place largely thanks to and in tandem with the implementation of neoliberal economic policies of privatization, trade liberalization and the deregulation of the banking and other sectors.

From Wall Street in New York to the City of London, to the financial districts of Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Hong Kong and Istanbul, soaring office towers, glitzy nightclubs and well-funded art museums are the urban manifestations of the rise of financial power. We should not imagine that this is the realm of the super-rich. The financial industry depends on and conscripts the labour of multiple other professionals, from lawyers to accountants, from computer programmers to management specialists, from janitorial service employees to sex workers. That is, not to mention the ways in which the money from the finance capital’s largess courses through the charity and NGO sector, or through the art world/market. Nor should we neglect the ways in which the speculative financial capital has inflated and accelerated urban property markets.

In addition to the growing size of the financial sector we can note a number of its profound and dangerous economic impacts. For one, financial firms have incredible power over the decisions and orientations of the corporate world; as businesses, large and small, rely on them for loans and to sell stocks and bonds. This power is typically used by the financial sector to transform other firms into engines for generating financial profit. Their demands to raise share prices often come to supersede concerns over workers’ rights, the environment or even the long-term sustainability of the company in question. But lest we imagine that finance is only the diabolical scheming of a conspiracy of shadowy bankers, we should recall that it is partly driven by the deposits, savings, investments and insurance premiums of workers and citizens at large. It is their assets that are leveraged by the financial industry to drive the whole economy towards the ever-accelerating maximization of profit, at any cost.

These effects of financialization are increasingly well known and widely bemoaned, but the anger towards the financial industry expressed by urban movements like Occupy and the Movements of the Squares has yet to result in meaningful change to government regulations. The reason why such regulations have not arrived brings us to the second dimension of financialization: its political consequences. The financial industry holds the purse strings in an age where nearly every government around the world (not only of nation states but also regions, provinces, cities and even school districts, universities and hospitals) is deeply in debt and dependent on new loans to meet their budgetary requirements or to initiate new projects. This gives it an incredible influence over policies, which are typically being used to drive the neoliberal agenda such as: demanding the privatization of services and the deregulation of capital (notably, of the financial sector itself). This is over and above the considerable amount that the financial sector spends on lobbying and directly influencing governmental actors. Furthermore, it is well known by now that the upper echelons of most governments (and certainly most financial regulatory bodies) are staffed by former employees of the financial industry and that many politicians begin their careers in the banking and finance sectors.

One of the woeful effects of this political influence is a widespread use of financialized language to express matters of public concern. Policies are increasingly guided by questions of ‘risk management’ and assessed on the basis of prospective ‘return on investment’.

Indeed, in some jurisdictions financial tools and measurements are being used to determine the success of policies and social programs. This leads us to the third dimension of financialization: a sociological phenomenon. Here, financialization escapes the realm of economics and politics and can be seen to be bleeding through and staining the fabric of everyday life, the public discourse and social institutions. Take, for instance, the dramatic society-wide transformation of housing over the past forty years. We have been taught to imagine our homes not as dwellings for our families or as parts of communities, but as privatized vehicles for personal, competitive investment. As the welfare state has eroded, leaving us to fend for ourselves in the market, almost all aspects of life have been opened up to the rhetoric and practices of a private financial sensibility. We are taught to imagine our physical health as an investment, to think of education not as a common social good but as a speculation into our own private future. Even charities and non-governmental organizations have been encouraged to understand themselves as engaged in venture philanthropy and social impact investment, beholden to and driven by the logic of the market.

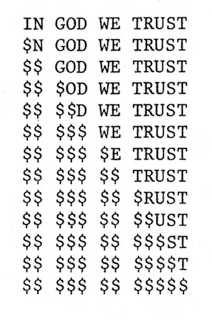

The financialization of practically every aspect of our social lives both depends on and contributes to a deeper cultural shift, one where we are all instructed to imagine ourselves and act in the world as ruthlessly competitive investors, responsible for subjecting nearly every decision and relationship to the austere measurements of the speculative market. Hence we have seen the publication of relationship advice books claiming that using the cold rationality of the financial world can even help improve our intimate lives or relationships between parents and children. We have also seen the rising popularity of reality television shows that lionize the savvy homebuyer1 who judiciously selects the most promising investment opportunity.

In sum, the cultural effect of financialization is to contain and diminish the potential of the future, to render it into a commodity to be bought and sold today.

It represents the triumph of consumer individualism where not only are all aspects of life rendered commodities, but we as social subjects become responsible for the never-ending risk management in the privatized bubbles of our own lives. And yet—and this is key—this grim new reality is not directly experienced as oppressive or disciplinary. We are told to love, enjoy and praise our individual financialized sensibilities and the sense of freedom, responsibility and power that we are allegedly entitled to under financialization.

As we have already seen, financialization has multiple overlapping implications for urban space, urban dwellers and urban movements, which brings us to the fourth dimension. For one, we have witnessed (especially, but not exclusively in the United States) the economic terror the financial industry can unleash on cities like Detroit. The financial industry first drove the deindustrialization of the city, promoting corporations to move car production offshore or to cheaper locales, and then subsequently pushed the neoliberal policies that led to tax cuts for the wealthy and the privatization of key services. But the financial sector was also the key creditor of the city, demanding interest rates on loans so extortionate that it led the once-wealthy city to file for bankruptcy and call for the wholesale abandonment of the citizens and the liquidation of public resources in the name of its own profit. Detroit is an extreme example of a city lethally sabotaged by financial capital, but one that gives us a sense of what is at stake.

Beyond such extreme cases we can see on a more practical local level the ways in which financialization is, to a large extent, both based on and responsible for driving the explosion of speculative property bubbles; especially in global cities like New York, London, Amsterdam, Los Angeles and Tokyo. It would be bad enough if the influx of speculative capital simply dominated the most desirable neighbourhoods, driving up the prices of purchasing and renting flats for the middle class and professionals. But we have also seen, in the period of financialization, a growing financial hunger for formerly undesirable neighbourhoods and the acceleration of the processes of gentrification, which enlist artists and other unconventional workers as shock troops to displace original, poorer (often racialized) inhabitants before they too are priced out of the market.

In many ways finance capital is fundamentally reorganizing global urban space according to its own image, transforming the built environment into so many temporary, disposable channels for fast money, with absolutely no care for the human consequences.

As David Harvey lucidly argues in his excellent book Rebel Cities,2 urban space has become the front line of a struggle against global capitalist exploitation in its financial and non-financial varieties. In Spain, for instance, a group called The Platform for a Citizen Debt Audit (PACD) represents a network of urban activists across the country who are independently performing audits of their cities’ debts, trying to parse out which debts are legitimate and should be repaid and which are extortionate or incurred by corrupt politicians and can be refused. Such initiatives attack financialization on all four levels: they represent a direct challenge to the financial industry’s economic power and legitimacy; they undermine the cosy relationship between the political and financial elites; they challenge the idea that all of society can be understood and managed as a speculative market; and they offer a venue to develop a culture of collective solidarity, as opposed to individual debt, alienation and fear.

These initiatives are connected to militant anti-foreclosure movements like the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) in Spain or Take Back the Land and Occupy Our Homes in the US that defend and accompany the unfortunate debtors, whose homes have been at risk of being repossessed by the banks and the financial industry in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Using techniques of direct action and peer-to-peer solidarity, these movements once again challenge financialization from a comprehensive grassroots position. They refuse to let the value of financial accumulation supersede the value of the human right to shelter and they protect the right of communities to decide on the shape of their collective futures.

Beyond organized movements we can see the emergence of some new micro-level politics of the city, which is promising but also ambivalent and ambiguous. A new generation of young people, raised under the aegis of financialization, is not hesitating to engage the financialized city on its own (often problematic) terms. The rise of start-ups, micro-businesses, pop-up shops and various forms of social entrepreneurship could well be understood as symptomatic of the financialized imagination. The entrepreneurial enthusiasm of middle class youth, blithely embracing the financialized ethos of our day and age, may see them become the unwitting agents of its relentless advance. Certainly the rhetoric and reality of many co-working spaces or social enterprises seem to reflect financialized ideals: the individualization of life’s risks and the transformation of each of us into an isolated speculative economic agent eager to plunge into the cutthroat marketplace and compete in a world without guarantees.

In these initiatives we have perhaps the inverted, neoliberal image of dérive; the practice of radical anti-capitalist psychogeography practiced by the Situationists3 in the 1960s. In order to liberate themselves from the conventional, habitual relationships and patterns of capitalist urban life, artists and intellectuals mapped and drifted through their cities in radical new ways. The new urban financial micro-entrepreneurialism likewise sees the city not as a hard and fast, bricks and mortar grid, but as a series of mobile and changeable assemblages, fluctuating and constructed relationships and ephemeral connections and identities.

But unlike the Situationists, who aimed to use their techniques to open up pathways towards revolt and resistance, these new forms of urban engagement aim, at best, towards the mere urban economic survival of an abandoned generation that has largely been excluded from any meaningful economic or political control over urban space.

The future of the city depends not only on our ability to carve out limited spaces of solace and autonomy under the totalitarian power of capital; it relies on us taking our revenge on capital for what it has done to our cities, our communities, our bodies and our souls.

I do not wish to be overly pessimistic about the often phenomenal and inspiring initiatives taken by young urbanists. Often these avow a commitment to social justice and create spaces for non-economic communities to grow and to flourish in the cracks and small spaces left to us in the financialized city. Sometimes they even speak the language of the commons and adopt the theoretical posture of radical social criticism. At best they do provide alternative forms of social cooperation and relationality that could, at least theoretically, prefigure something new.

But I believe it is important to assess these initiatives skeptically. Do they empower us, as workers and as communities to resist and revolt against financialization in meaningful ways? Or do they simply create zones of temporary comfort in a heart-breaking world? And who, in reality, do they serve? Who do they exclude when it comes to questions of race, class and gender? As both the global economic and ecological crises deepen, I fear we do not have time for a jejune celebration of individualistic solutions to complex systemic problems. Financialized capitalism is not a monolithic juggernaut; it is a complex, multi-faceted, contradictory and highly adaptable system, but one that needs to be overturned.

If we wish to look to new forms of urban resistance and innovation, we should instead turn to the resistance of refugees. All refugees today are also refugees from finance and financialization, from the way the power of financial capital is driving and benefitting from imperialism and transforming whole areas of the world into economic or ecological wastelands. Even though financialization appears to be a borderless force that undermines the sovereignty of nation states, it relies on and manipulates borders to attenuate the flow of humanity in the interests of corporate profit. As Harsha Walia4 notes, refugees by their very act of refusing the imperialism of borders, fundamentally challenge the financialized order. They are generating new forms of grassroots power through their daily struggles and the solidarity they must build to survive in often hostile cities where racism is on the rise. The question now is whether and how a young generation of precarious urban subjects working in the cognitive or service sectors can build a common cause with refugees and together take aim at the financialized order that renders them both disposable – but not equally disposable. Such solidarity must be based on true collaboration, humility and militancy within the space of the financialized city.

- Video fragment: Location, location, location (2014) TV trailer, Channel 4. ↩

- David Harvey (2013) Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, Verso Books ↩

- Wark McKenzie (2015) The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International, Verso Books ↩

- Harsha Walia (2013) Undoing Border Imperialism, AK Press ↩