During the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale, entitled ‘Reporting from the Front’, Dominika Janicka in cooperation with Martyna Janicka and Michal Gdak curated the exhibition ‘Fair Building’ at the Polish Pavilion, taking a close look at the ways in which architecture is made and the rather questionable conditions in which the construction industry operates. – Read our conversation with Michal on the possibility of fairer architecture.

AM: How did you arrive at the topic of the exhibition, and why did you want to look at the aspect of fairness in the construction industry? Was it something you were thinking about before or was it strictly related to the theme of the Biennale?

MG: Dominika came up with this idea in response to the theme of the Biennale and its title ‘Reporting from the Front’. Reading the title literally, the manual workers are for us the first ones at the front of architecture. There is a huge amount of people involved in the process of construction, including engineers, architects, investors and developers, but manual workers constitute the biggest group and that’s why we decided to focus on them in the exhibition.

CA: Is the condition you describe specific to Poland or is it something universal?

MG: The exhibition tells the story of Polish manual workers, but we strongly believe that these problems are the same all around the world. Of course certain abuses or problems present in the construction industry can be more or less serious in different countries, but in this case Polish conditions serve as an example that we hope will spark a debate on this topic. Fair Building refers directly to the Fair Trade movement, working with the incentive of earning the approved status and logo to show clients that your products are made in good conditions and that workers involved in the production process are paid fairly. There is nothing like that in architecture.

AM: There are sustainability standards, but they mostly focus on materials and buildings’ performance, not on labour and the legal situation. There are no standards that relate to workers’ rights, contractors’ responsibilities, and how the workers are – or are actually not – protected in the system, which they are at the base of.

MG: Exactly. These are the most important questions of our exhibition. Working on the proposal we were inspired by two interviews that appeared at that time and became quite important for us in defining our approach. One was an interview with a member of an association of crane workers in Poland, published in one of the national newspapers. It turns out that it is the only group in Poland that has a union among all construction workers; none of the other branches of the architecture industry has a union!

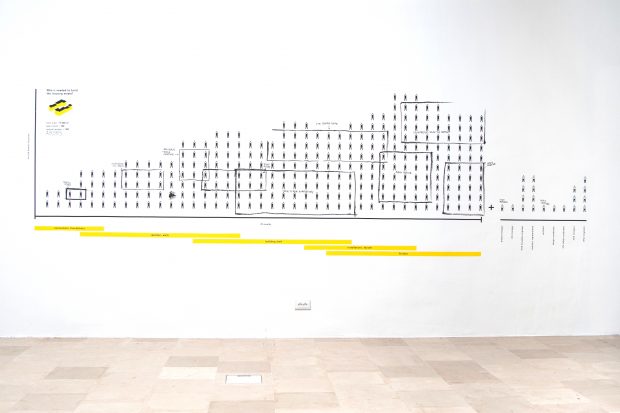

It is actually very difficult right now to create a union or any kind of workers’ organization in Poland, and perhaps also everywhere else. As we have shown in the diagram presenting the structure of the industry, the general contractor usually works with many subcontractors who each hires from three to fifteen people on average; it makes it very hard to get together in one union. Effectively the workers have a lot of difficulties fighting for their rights, and when we interviewed them they admitted feeling completely disempowered.

AM: This is perhaps the biggest problem, isn’t it? That they are accepting the situation as it is, because they don’t think they have the power to demand better conditions.

MG: Indeed, but those crane workers do it! They have official meetings, exchange information and fight for their rights. Of course they are highly skilled, and their job is important as well as dangerous.

Which brings me to the second interview that appeared while we were working on the subject. It was the interview with Zaha Hadid on the BBC radio, when she was asked about the injuries and workers’ deaths on the construction site of her building. She was really annoyed by the questions and responded that architects were not responsible for this. Maybe governments or developers should take care of it, but not architects. So our next very important question was: who is responsible for the conditions on the construction site?

AM: Did these interviews point to any clues in terms of what is missing and what could be done? Did you have any ideas responding to the things that you did not know that existed before reading these interviews?

MG: First we did some research at the construction site, talking with the people there. We even stayed at a labour hotel, where the workers live from Monday to Friday; on the weekends they go to meet their families living in other parts of Poland. We tried to be as close to them as possible in order to understand the conditions in which they have to work. That became the first part of the exhibition. We presented five movies among a scaffolding structure; four them were shot with GoPro cameras mounted on workers’ helmets and a first-person narration where the workers speak about the different kinds of problems they experience. Of course they are generally concerned with very common topics such as low pay, injuries, black labour, lack of contracts and so on. What really surprised us, however, was the disrespect they experience. It seems that everybody in the construction industry thinks that the manual workers are the last link in the chain of architecture that they do nothing and are not educated well enough. In one movie a worker describes an incident where a passing woman says to her child: “If you don’t study, you will be digging ditches”. In fact the lack of respect is the most saddening aspect for them.

AM: I find it really unfair, considering that so many people are disconnected from manual labour. It is not surprising then that so many Polish workers decide to migrate.

MG: Many people whom we spoke to decided to stay in Poland because they love the job and have a passion for it. It is also important to note that people working with passion often achieve a better quality of the work, which means that the construction is more precise and follows the architect’s directions on final appearance and detailing more closely. We also found out that the connection between the manual worker and the architect is often broken; there is no fluent exchange of information between them. This is also represented visually at the construction site, where yellow and white helmets mark the division between engineers and manual workers.

CA: How does this topic relate to the rest of your work? Do you have a fascination with similar topics or was this a first experiment?

MG: As architects, Dominika and I regularly deal with the work on construction sites, maybe not as big as the ones we visited during the project, but it was not something completely new to us. However, this exhibition has totally changed my relationship as an architect with the construction workers. The possibility of being closer and understanding them better was actually transformative.

AM: You also have background in sculpture, which I think is defined by being very tactile. Is this becoming something that we have to look at more in the process of making buildings, could it help us reconnect with the way things are produced?

MG: What sculpture has taught me is that what is made with your hands, what is touched, is an experience that cannot be repeated in theory, in a computer model or simply represented as data that can be found on the internet. Having the experience of materialization can definitely create a deeper understanding of how manual workers, sculptors or artists work.

In the second part of the exhibition, we focused on the most generic experience most people have with construction, where developers sell the appearance of a building and the buyers don’t realize how it is constructed and materialized. We show it with a beautiful visualization of a real estate development, presented right opposite to the diagram describing labour relations in the construction industry, with all its abuses narrated in detail by the protagonists of our movies.

AM: Do you think that showing the scale of abuse can provide a stimulus to change legislation regarding workers’ rights?

MG: Change should come from different directions. As I said, at least in Poland workers are not really fighting for their rights because they don’t believe it is possible to fight against an established structure. But chambers of architects, developers, investors and engineers could work together to provide a direction for addressing these issues

CA: Isn’t there a conflict of interest though? Architects can of course support workers’ rights, but they also count on the cheap or even illegal labour to secure lower prices for their commissions…

MG: I would say that this contradiction belongs not only to architects, but mainly to developers, because it is actually their business to build the building at the lowest price; they get the most money out of it. For our part, we are attracting the interest of organizations like the International Labor Organization, UNESCO and Amnesty International, because they are already doing work that showcases these situations around the world, including in Asia, Latin America and the Arabic world.

AM: The quality of design and construction is often compromised for profit maximization, but people still buy these poorly realized properties, because they do not seem to have any other choice. Are there possibilities to prevent the liberalization of the market, especially when it comes to housing, in order to control the quality of the buildings that eventually create the cities we inhabit?

MG: We are just at the beginning of finding some answers but I don’t know if it is actually feasible to find regulated solutions here. Bringing together all the actors involved in the construction process is really complicated. For us the exhibition functioned as an invitation to collect more stories and information; in the end, we would like be able to answer the question: ‘Is fair building possible?’

CA: How do you plan to continue with the project now that the Biennale is over?

MG: We try to get in touch with all relevant organizations. We took this subject up because it is also important for us to start this discussion. However, as architects we will probably also be engaged in other projects in the years ahead. Therefore we would like to give the information we collect to the right people who can continue this debate.