ZUS merges the theoretical and practical aspects of what we today call city making, yet they are also a design office for architecture and urbanism. Together with ZUS principal, Kristian Koreman, we discussed the ways they combine the two, how it was to be at the forefront of emerging unsolicited architecture and what do they mean by the necessity of engaging with unobvious design tasks.

AM: ZUS is not a typical architecture practice; you are strongly involved in a theoretical debate and you actively communicate this as a part of your practice.

KK: The starting point of our projects since 2007 has been the writing of our manifesto: the book ‘Re-Public’, which describes our new role as architects operating in between the private and public spheres, the market, the citizens and the government. Initially, we did not acknowledge it as our agenda, but for the last few years, we have been acting based on this rather lucid rhythm. Now, we are writing a new manifesto to update the ideas that are in there, so that theory becomes practice and than it can be theorized again.

CA: The theory is not the only thing that defines ZUS, you pair it with a hands-on approach.

KK: Yes, it is fundamental to us to jump right in the gap between the academic world and architectural practice. I don’t mean architecture and urban academics, but more political science or economics and the urban reality in which we have to act as architects and urbanists. That is the domain that we want to work in and explore. We always start with theory, with an ideal, a kind of utopia and then try to tie it to reality. It has always been hard to connect the theory and reality; theories tend to be rather absolute, like the radical reality of market driven developments or its critique or the absolute green, sustainable utopia, none of which really benefit low income groups or the majorities of society.

AM: A utopian idea can have a very large scope when put in to practice. I suppose your approach is not based on a utopia that attempts to fix the world, but one that provides a starting point, a desire. How do you find the translation from the ambition of that desire to a project that has a realistic scale?

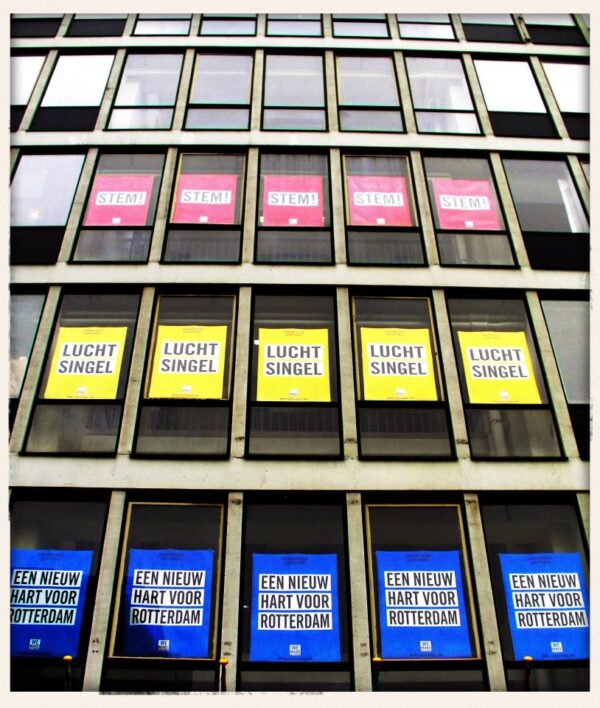

KK: Our approach can be described as doen-denken (doing-thinking). It is a constant process of thinking by doing, where both are of equal importance. In the example of the Luchtsingel, we had an idea to connect three neighbourhoods, because they were separated and because there was a lot of indifference towards them. It was a big idea. This story would sound crazy to a politician, but we needed it to start talking about the bridge. Ultimately the bridge is an object but it needed a story that is perhaps more than a utopia; it is a really strong narrative, which binds a number of complex issues.

CA: The career of ZUS started with taking up unsolicited projects. Even though more groups seem to have the courage to start that way, it is still an unusual way to start an architectural practice, can you tell us how it all began?

KK: In the early 2000s we were occupying one of the numerous empty buildings in the middle of the city centre, while the municipality was making plans for a city with plenty of new skyscrapers, more cappuccino spots in public spaces and strollers everywhere. These plans had already been announced as the new future for Rotterdam.

We wondered how was it possible that the representatives of the real estate market and the government thought that this plan made sense. We didn’t think it made sense at all! This frustration motivated us to create alternatives that would question the feasibility of the plan. The celebration of cultural diversity in Rotterdam became our focus and we started working on plans for areas where we saw this quality was neglected.

In the times of the Superdutch generation everything one could think of could be built without asking for whom or why is it being built. We really wanted to be critical towards this way of building. We see the architect also as a public figure and think that since 1989 this public part of the discipline has been neglected.

CA: Why do you think that it has been neglected?

KK: Because the neoliberal mechanisms generated an ease to build spectacle architecture and promoted a non-critical point of view, which continued unquestioned until the crisis and the Occupy Movement. I think it was partly due to the laziness of our profession that can be summarised with a statement: ‘Ok, I will design this building, I know that there is no demand for it, but I will do it for my client anyway.’ But after all we are citizens, not only architects.

We are part of society and we need to bind our political agenda to our work.

AM: How do you bring this political agenda to reality?

KK: We often write letters to ministers and other officials about the responsibility they should take. We also try to get our stuff published, not in architectural magazines, but in local newspapers, which we find much more relevant.

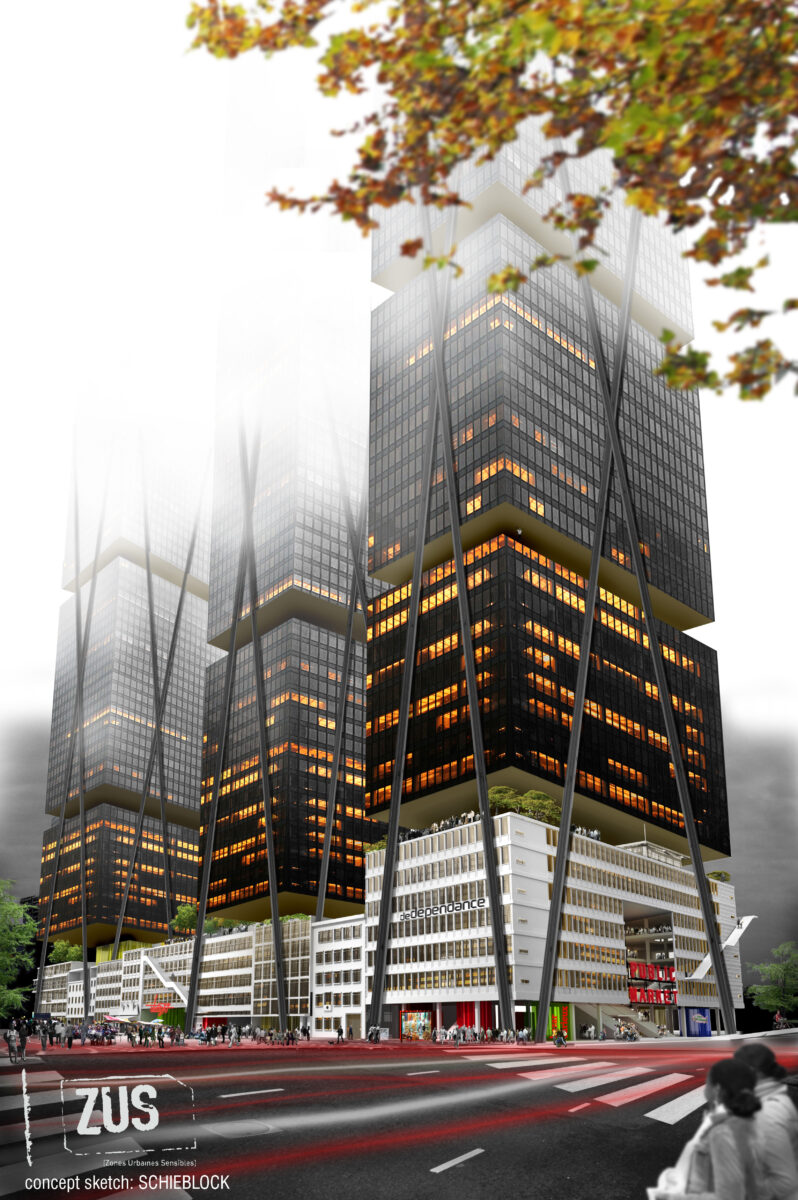

In 2008 at the Venice Architecture Biennale we presented a vision for the development of the Schieblock area that was an alternative to the one where everything had to be torn down. We made a suggestion to start with the local economy as a basis. Because municipal officials considered our proposal a debate was opened.

To make our ideas concrete, we focused on one building (the Schieblock), because it was the first to be torn down and we already occupied it. We decided to start our own development company and test what it meant to be a developer. We set up Schieblock Inc., built a model of the building, opened an info shop on the ground floor and asked people if they would like to rent a space in there; nothing sexy, just a key and the walls, that was it. The plan was very practical but at the same time it complied with the political framework that advocated mixed-use, green roofs, connectivity, cappuccino, place-making and sustainability – all the nice key words. We called the project an urban laboratory and within three months we had enough potential tenants to run the building. It took hell a lot of work to make it function, mostly because we had to learn by doing, but ultimately we have a very successful building.

AM: Nowadays the connectivity that comes with the internet enables building coalitions for bottom up or community-based projects, also crowd funding has become one of the ways to realize architectural projects. Do you think that these will continue to play a big role in the next 5-10 years?

KK: The crowd funding of the Luchtsingel was for us a small part of the whole project. It was important, but very different from what you usually find on platforms such as Kickstarter. Those are mostly art projects and products, like a new fancy watch or a remake of a film. I don’t see many really good projects on these platforms, probably because the interest of the initiator remains very personal. Perhaps in some ways people have forgotten how to engage in the public’s interest. Ultimately doing something public comes with a lot of consequences. Now, everybody is building platforms, but what does it actually mean? How can you make sure that such a platform goes further than being a place where everybody just ‘likes’ stuff and does nothing more?

We want to have an effect on reality.

CA: There is a lot of debate on the legitimacy of crowd funding of public spaces because the investors are often people who ultimately privately profit. What are your thoughts based on your experience?

KK: Since the WWII the Netherlands has been one of the most top-down organized countries in the world and now we risk ending up at the bottom of that list. Using the crisis as an excuse, the narratives of the participation democracy and do-democracy came forward, but that’s just because the state doesn’t have the power and the money to make public investments anymore.

In the case of the Luchtsingel it was much more than the crowd funding itself, it was about creating a public space out of an area that had been neglected by everyone, even the citizens. You can do this by organizing events, and of course, that’s what we did. But how does one go a step further and establish a sense of ownership without establishing the property? In our disclaimers we state that no one is a legal owner of this public space. On the other hand we aim for multiple ownership. Almost 10,000 planks of wood were sold to about 7,000 buyers. We believe in a model where corporations, institutions and citizens can share ownership for 25 Euros per plank. The model is open to anyone. For example, someone who instead of buying an expensive engagement ring bought a plank for 25 euro. Because of that it has ultimately become a kind of vernacular project as well.

We have to be very critical about when and how parties other than the government invest in public space, because it always introduces an aura of exclusivity. In the context of an economic crisis such as shrinking cities and growing numbers of vacant office towers that will never be occupied by big companies again, how do you come up with a new basis for self-organization? I think this project is an argument for another way of collaborating between the municipality, corporations and the citizens.

AM: Was there an important lesson you learned from realizing the Luchtsingel that you would do differently if you had a chance to do it again?

KK: I think it would be the intensity of the project. We invested a lot of time and took a lot of financial risk that we could never do again. In that sense it is a once in a lifetime project. We will never go as far now in terms of the financial responsibility. Everything went well after all, but it could have easily gone the other way. If this project had failed, ZUS would also have been ruined.

When the project left the paper and became real, it required dealing with finance and politics. Design was really the easy part, but entering the political arena when the project is out there takes real responsibility with regards to the media and everybody else, we had to partly become politicians ourselves and that has had a big impact on us that was not only positive.

Social media is a great tool, but if it works against you it can get very heavy and personal. If we were to do the project again we would definitely hire specialists to communicate for us like politicians do.

AM: You received some criticism on social media during the process, but now that the project is nearing completion, do you get more positive reactions?

KK: The cultural rooftop park at the end of the route is still the big promise of the project. We have already seen a positive change in opinion in those who were initially critical of the project. There are a lot of people who mention that they had never been in these places before. It is striking that the project is located at the geographical core of the city, and yet nobody had ever visited. It proves that we have turned a blind spot into a new address. We are also very happy to see mothers with children there. With all the infrastructure and large surrounding buildings this is not a place where you would normally go with a stroller. The fact that people start to appreciate it is the biggest compliment for us. People have been married on the bridge and dedicate marriage or a birth planks, these are rather sensitive, sentimental actions, which we would have never expected in such a brutal environment.

CA: But it is still an environment where people live, so these are also expressions of the desire to appropriate their living space.

KK: Absolutely yes. I think for us a good design addresses an unfulfilled or a latent need, that has never been expressed but now becomes visible. I think that a sensitive designer knows what the needs are and makes them explicit in the design. It is not about the demand, but about the potential of the place that can respond to a need.

CA: A lot of your projects are in Rotterdam and the way you work strongly relate to the identity of the city. How do you see the relationship of being very local on the one side and having a broader perspective on the other; how does Rotterdam come to define your work?

KK: Rotterdam has made us. If we had ended up in a beautiful office in Amsterdam we would definitely have produced a different kind of work. The sensitivity we have towards our context is definitely related to where we came from.

Rotterdam seems to be like an indicator species in an ecosystem, it is the one that feels the changes before others do.

This city is a laboratory where things happen in front of your eyes. We also claimed it as our laboratory, because we were intrigued by the socio-economic processes taking place here and the way they relate back to architectural production. So for us Rotterdam is a perfect place to ask questions, test, make projects and relate this experience to other places. Rotterdam will always be our headquarters and the fact that we have been invited to work in the United States and in China is because of our work here. If we would not have our roots here the branches would never have come. That’s what we believe in: investing in the roots in order to grow the branches.

AM: How do you complement the deep insight and the sensitivity for the space you know very well, when you have to transfer your experience to a completely different context? How do you find ways to adapt what might not be a one-to-one translation?

KK: It can never be a one-to-one copy, but the logic behind the projects in a more abstract sense is no blueprint. It is a multifaceted strategy, which is more user based than investor based, more temporal than permanent and looking for a complexity of issues rather than a limited agenda. These are lessons that we can definitely take to different contexts and find local stakeholders to tap into their knowledge.

We know what the important steps to take are and what the tools are to discuss both with the bottom and the top. The project we are currently realizing in New York is really based on these principles: having a big idea, having a strong public structure as a spine of the project and binding everything to it. This spine does not describe the whole project but it describes its core. The core very strict but what can happen beside that is very open. It is a physical, but also economic and political structure which we want to control completely, like we do in the case of the Luchtsingel, all the rest can be much more adaptive. We described it in the book as two forces that go hand in hand: the Monarch and the Anarch. We believe that they have to be taken into account in every project and we need to make sure that the king and the anarchist talk to one another.

CA: Do you think that the role of the architect will transform from delivering a design to mediating between stakeholders? Will the city makers of tomorrow be different from the ones of yesterday?

KK: I think the city makers of the past were the governments with one or two big architects. The ones of the future will be more urban curators who will be able to bind different agendas in one location, and form specific agendas for each project. I think that we still see ourselves as an exception. We don’t know if what we are doing at ZUS can be a part of a bigger reality, but we feel that the lessons we have learned can be applied elsewhere. Even though the whole system in which we work is still breathing the traditional roles of the planner and the architect, where things are changing very slowly, there will be more of the places that will not ask for a clear design brief of a market hall or an office tower. Those potential projects are definitely new ground for a new type of city maker, because they will be out of the scope of both the government and private investors.

CA: Are you optimistic about the future of the cities? What do you think is the major issue today, and how do you think they are going to develop?

KK: If you read Piketty’s Capital, translating his findings to the urban reality, leaves little space for optimism. In essence, we are really optimistic people and we believe that once architecture and urban communities start working on the less obvious projects, where there is something to gain, we can be positive. However, if you look at the big picture, which includes flood risk and social inequality, are open to that reality, you see that things really have to start changing radically if we want to be able to fulfil the basic needs of the human population. 95 percent of the architecture community is still focused on the obvious projects. There is only a small share of projects that deal with big issues, not with new fancy apartment buildings with new 3D printed balconies. Of course we also like to make really nice designs with innovative materials, but there is still a huge gap between the focus on a limited part of the architectural production and the real needs. I hope this changes, but maybe the crisis has to become deeper so that we can achieve that. Maybe more architects have to be unemployed to start thinking differently.