AM: Could you tell us something about your latest projects?

DH: Recently I have been thinking a lot about different ideas of time and its standardization. I have realized a few projects related to time zones and time distribution. In one of them I melted an old bell; in another I moved the border of the Pacific time zone; and in a piece for Eva International I aimed to remain in California time while being in Dublin. In that last example I tried to adjust my rhythm set to Pacific Daylight Time to the local time in Ireland, which was obviously completely out of synchronicity with everyone around me.

CA: You mentioned ‘Let Us Keep Our Own Noon’ (2013)1 where you created an installation from an old bell from the eighteenth century. This example relates to the idea of place and time in a physical and conceptual way. In other works you refer to different concepts of space, could you tell us a little bit more about that?

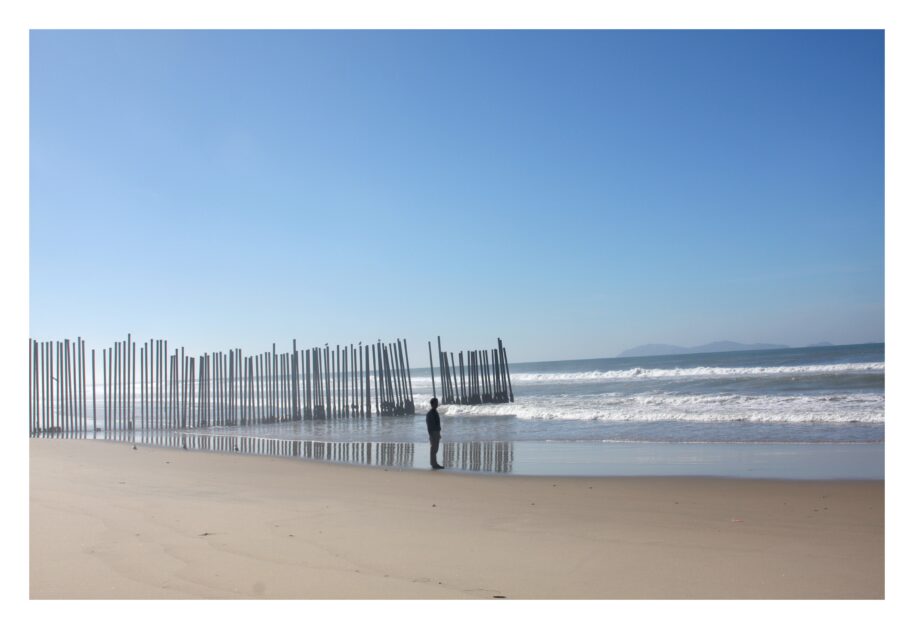

DH: For example in ‘Public Access’ I took a set of photographs of Californian beaches and uploaded them to Wikipedia. This time I wanted to work with public comments online, participation and the culture that is produced by the people who create online content on Wikipedia. I wanted to take a look at the places of digital circulation as well as the physical ones. Eventually ‘Public Access’ linked the publicly accessible coast of California and Wikipedia as two different kinds of public space.

CA: I find the way you used the public sphere of the Internet very intriguing. Even though the Internet does not have a spatial location you seem to you use it in the way that a street photographer might use the street when taking pictures of strangers.

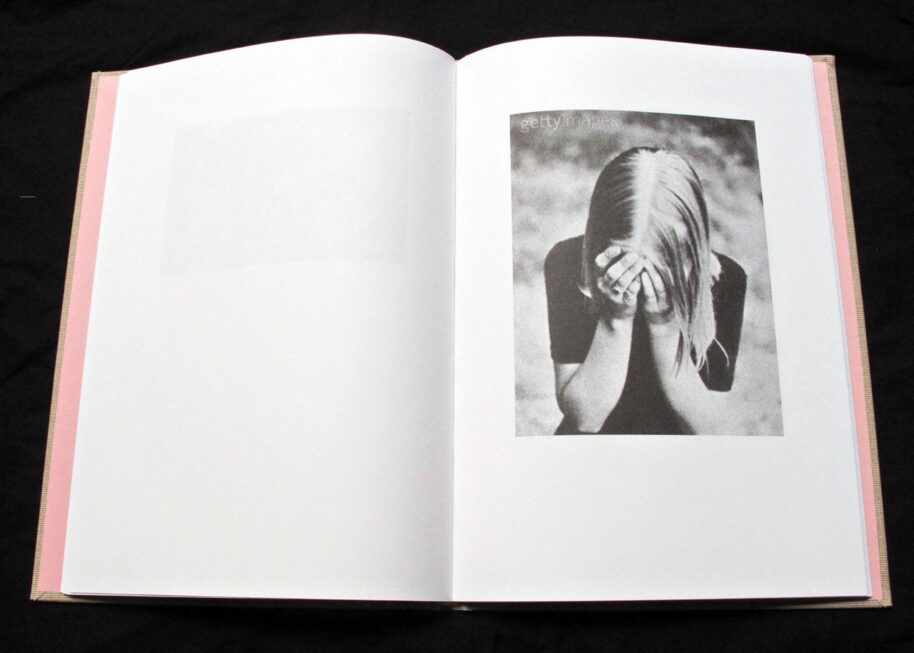

DH: I definitely used that approach in two projects I did about depression. The first one, called ‘Sad Depressed People’ was about collecting stock images of depressed people. These images were public, in the sense that they were published online, but in fact they were not public at all because of their copyrights. I wanted to understand how these images visualize the idea of depression, mood disorder or feeling bad. Normally stock photography serves as a general reference or a substitute of an authentic image. But it is often used in advertising where you usually depict something positive, something that the viewer would desire or would relate to. A picture of depression is not marketing something you want. It is something telling you who you are. By looking at these images I tried to decipher what depression is and how it is depicted. There are clichés, like the lone person with their head in their hands. Or a certain contrast and color – or location, like at the sea, or sitting alone in an open landscape. And there are a lot of images of depression that depict businessmen and a kind of professional failure. Maybe this is the contemporary form that sadness takes, despair from a failure in business, a failure to make profit, a failure to keep up.

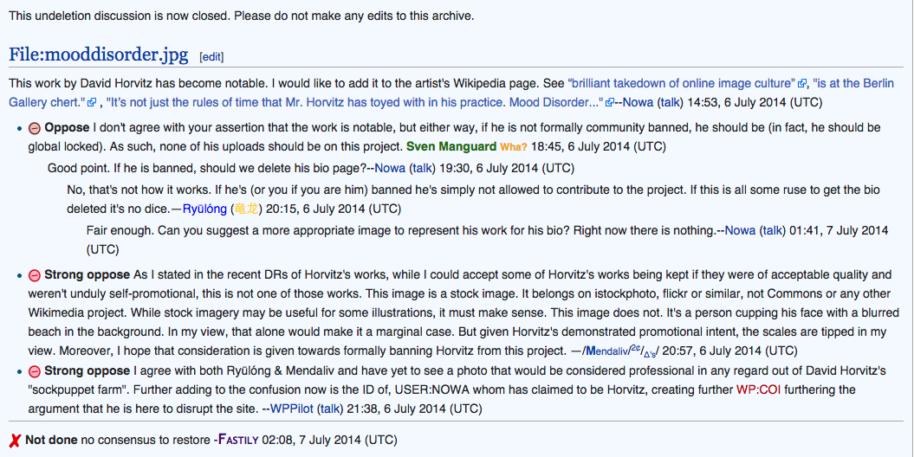

This led me to the second project called ‘Mood Disorder’. This time I took my own photograph, where I acted out a generic image of depression from the photographs I collected in ‘Sad Depressed People’, and published it on Wikipedia. My image was similar to the other pictures but through Wikipedia it became free of copyright. That basically made it a free stock image, which began to circulate on the web and was used by websites that take free content from Wikipedia.

The main difference between those projects and the ‘Public Access’ is that the latter was very much about being active on Wikipedia, while ‘Mood Disorder’ was putting an image online to let it circulate from Wikipedia into the public sphere of the rest of the web. I see both of them, however, as metaphors for a seed. In that sense these projects can never be finished as long as the images circulate online and I think this is true about many of my projects. My works are hardly ever done when I finish them, most of the time I let them go and they continue to manifest themselves on their own.

CA: Can you tell us more about the ‘Public Access’ project? You planted the seed by uploading the pictures to Wikipedia and then observed the editors’ reactions without getting involved. How did you later notice that people were puzzled by your activity?

DH: When I was driving up the coast from Mexico to Oregon I took photographs of different beaches along the way. I did it in such a way that I was visible in every image as an anonymous figure that just happened to be there, standing and looking at the ocean. I was always either turned around or in the shadow, in the margins of the image, and always outside of the main subject of the photo. I uploaded the photographs into relevant Wikipedia articles about the specific beaches. I don’t exactly remember how I first noticed the reaction of the Wikipedia editors’ community that tried to make sense of my activity. They realized I was uploading these photos and got into a discussion about the legitimacy of my action. They could not deny I uploaded content relevant to the articles but they assumed I was making a joke.

AM: Had you expected that sort of discussion would emerge when you started uploading the images?

DH: No, I honestly didn’t think anyone would notice. But it turned out to be an interesting discussion! They were basically debating whether my images were legitimate, whether they were breaking any rules. But first and foremost, they were discussing this in order to decide a course of action: would they delete my photos or would they keep them? In the end they deleted them because they argued I had broken the rules. Actually my photos didn’t break any rules. There is a rule about using recognizable people, but all my photos were of me, and I was always anonymous. My head was always turned away from the camera. The rule I broke was that I was proving a point. I guess there is a rule that says you can’t use Wikipedia to prove a point, and I guess that is what I was doing. But there were many people who defended my photos, who said they were useful to the articles that lacked any imagery, but their voices were overpowered by the overwhelming consensus of these editors – that I was fucking around on Wikipedia, and Wikipedia is their turf, and they had to defend it. Though, maybe this ‘overwhelming consensus’ was just one really loud user, or a couple of them….

CA: You made two books based on that project. Wikipedia is a virtual environment, one that is constantly evolving. How does it look printed on paper? What happens when this perpetually edited document is transferred onto a medium that is associated with permanence?

DH: Who knows what is more permanent: the paper or the Internet? I do recognize a special quality in printed documents and perhaps you can read it in the story of one of those books. It was realized with the help of my friends whom I asked to print the Wikipedia pages of ‘Public Access’ on their office printers. Those prints were scanned and compiled into the book. I wanted to use different printers because office printers often have a mark that appears in the same spot on every print. To me that revealed a really personal aspect of something regarded as impersonal. I also always keep a time stamp on the images to preserve the trace of content that exists at a certain moment in time.

In another project (related to ‘Mood Disorder’ but using a different photograph) I made one printout per minute of the Wikipedia entry on melancholic depression, containing the image I made, for one hour. Obviously it was the exact same print but the time stamp was different, so even though the image was taken from the Internet, there was some kind of unique quality to each individual print because they were all made at different moments in time.

CA: You already mentioned that one project sometimes becomes the offspring of another. When you start a new project like that do you ever think that you wish you had known something before you’d begun, or do you prefer to treat it as a natural part of the working process?

DH: A lot of my work is improvised so I never work with problems that were there before. I create new ones every time and just move along.

AM: So each project is a personal process of learning by doing, and you aren’t disappointed if you fail, because it’s just a part of the process…

DH: Yes, totally! A lot of times, I don’t have an ideal situation where I want to end up, I just work my way to a final point, even though I can never know in advance what this point will be. I don’t think I ever had those idealistic yearnings of “I wish I did this…”. I just figure out things as they come.

CA: If you never complain about things that you wish you had known before, what is it that you complain about the most?

DH: I don’t like to complain, but I do consider some things annoying. For example, the fact that we are always accessible. I don’t want to have an office job to wake up and write e-mails the whole day. I find that stupid. I have to admit that it does actually take up a big part of my time, but to me it contradicts the idea of a creative practice and I consciously try to resist it. I think that art is ultimately about being in control of your time.

What I think artists need the most today, and in general, is time.

CA: You said time-management and constant availability are important problems at the personal level, what do you think are the most significant problems facing cities today?

DH: I live in New York City. All I see when I look outside of my window is concrete and asphalt, it’s like suffocating the earth. If it wasn’t for the people I like to have around me I would want to live in a little mountain town, on the beach or in a dessert.

CA: Do you think that cities might improve in the future?

DH: I really don’t know. Everything is changing… Cities like New York have a lot of problems. Many people have a romantic image of being an artist in New York that comes from a different time. In the 1970s you could maybe have an inexpensive studio in SoHo, live cheaply and make art. Today the city is so expensive that you have to figure out how to finance the sheer idea of being an artist in New York. I did this series of editions, and still do, where I sell an edition of 10 works at 10% of my studio rent. I do this every month: just a small piece of ephemera or something. Maybe a side thing of another work I’m doing. And if I sell all of these, then that pays for my studio rent. Some people have collected them all since the beginning, and they’ve got this tiny little mail art collection. It’s so messy. Some crumpled up pieces of paper, or some photos, or bent envelopes. But when I look at it, that’s all my studio rent…

AM: How does the fact that you located ‘Public Access’ on Wikipedia and the landscape of the coast relate to the diminishing amount of public space in the city? From your choice one might read that the city is not associated with public space any more.

DH: You’re right, but I also have to say that in my lifetime I never saw a different city and the fact that all the beaches in California are public is very specific to that state. Obviously there is a loss of public space, but it’s hard for me to say that I have experienced that loss in my life. Nevertheless, I would oppose the statement that there is no public space anymore.

What is public space after all? Is it just a space with a label ‘this is public’? No, it’s something that is actively made. Being public is not a spatial characteristic.

A park may be public but it becomes more public when a 1000 people create a temporary community in that park. It’s not the space itself that is public; the space becomes public through its use.

- Feature Image: David Horvitz, Let us keep our own noon, 2013, Installation View at the New Museum, New York, Courtesy the artist, Chert, Berlin and New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley ↩