Cities and architecture are not devoid of politics. Produced and governed through political processes, they often become the canvas upon which power is mapped. But this can also backfire. A square, designed to provide the setting for showing off the architectural grandeur of an institution, often becomes the very place where the populace gathers to protest directly against the powers that be.

In the same way that power is represented through the urban form, the occupation of iconic urban spaces directly challenges the power structure by contesting the functions and symbolisms of that space, as in the example of the student occupation of Tiananmen Square in 1989. The choice of protest space can also highlight the cause, as in the case of the occupation of Zucotti Park in 2011, a semi-public urban space owned by a corporation, which the Occupy movement chose to illustrate the social inequality caused by irresponsible financial practices. The Occupy protest gave Zucotti Park a new meaning, making it an icon in its own right. It challenged the significance of the space by filling it up with bodies that were not supposed to be there.

Protesters participate in city making, but what does it mean when protesters refuse to contest the space, and instead choose to politely hover just beyond its boundary?

Bersih 4

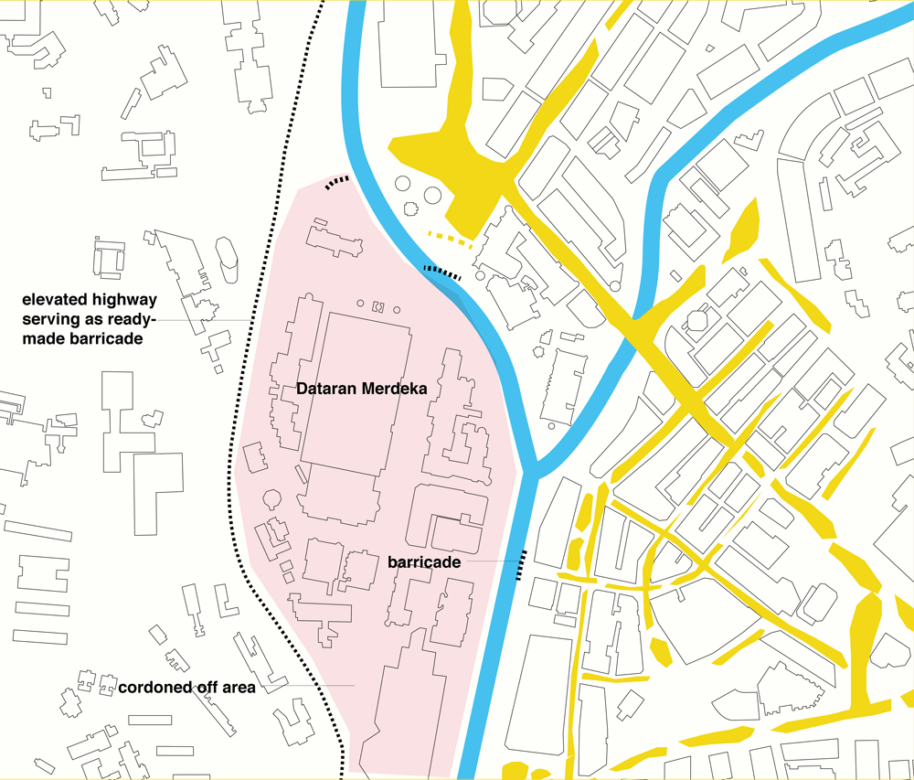

I thought about this question as I was observing the Bersih 4 1 protest in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in the final days of August 2015. The authorities did not give Bersih permission to organize the two-day long protest in Dataran Merdeka (Independence Square) in central Kuala Lumpur. The City Hall stated that Dataran was unavailable on those dates (29 and 30 August), due to preparations for the celebration of Independence Day on 31 August. Instead of contesting the space, as they tended to do in the past, Bersih complied with the decision and chose to occupy the vicinity of the square instead. In previous protests, directly defying the authorities had at times resulted in violent clashes – with Bersih participants cast as anarchy-loving troublemakers, a charge which obscured the cause of the protests. By avoiding a clash and not giving the authorities any semi-legitimate reason to throw them out, attention could be fully focused on the cause of the protest, which called for a structural reform of the government due to the 1MDB financial scandal2, involving public money.

Serious about complying with the authorities’ demand, Bersih set up their own barrier to the Dataran, about 100 meters from the one installed by the police, forbidding their own protesters from entering the space. After one of the protesters broke through the Bersih barricade, it was fortified by a human chain, adding an extra layer of protection. In the occupied road-space several clusters of protesters with different activities emerged, such as workshops on activism, experience-sharing sessions, or ad-hoc exhibitions of protest posters. The biggest crowd-puller, though, was a makeshift stage where the organizers and opposition politicians gave speeches, and where performances, such as singing and stand-up comedy, were carried out. The cool air brought by the night was a welcome contrast to the oppressive tropical heat of the day, making the space more festive. As the crowd grew bigger outside the barricade, Dataran Merdeka remained empty save for the rehearsal of the state-sponsored Independence Day celebration.

Symbolic space vs meaningful place

Dataran Merdeka is an impressive rectangular space located in the midst of a more organic urban fabric and defined by rows of colonial buildings. Formerly known as the Padang (‘field’ in Malay), it was a British colonial spatial instrument of town-planning employed in British Malaya, serving a number of functions from military drills to cricket games. The name was changed to Dataran Merdeka to commemorate independence from 450 years of colonial rule. The Dataran is thus loaded with constructed meaning: spatially representing the might of the Empire during colonial times, the celebratory name change after Independence signifies the triumph of the nation in prevailing over the former colonial masters. Due to its perceived importance as a national symbol, its use and function are highly regulated, so that only spectacles such as the Independence Day celebrations and revenue-generating corporate events are typically allowed. Since the Dataran has served the state as a rallying tool of nationalism, not as a space of independence, its opportunity to become a true public space has been lost. The space is not yet independent.

On the other hand, the adjacent space which eventually became the focus of the occupation is actually a big road junction connecting the more symbolic Dataran with the spaces of everyday life such as Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman (TAR) and Jalan Tun Perak. Humbler in scale, these streets and small squares form a representative segment of the historic core, where people go to work, shop, play, and live their everyday lives. These spaces also carry vestiges of colonial practice, such as segregation, with Jalan TAR associated with the Malay Muslims, and Jalan Tun Perak serving as the border between the Malay and Chinese communities. However, a closer inspection reveals that these borders have been slowly blurring, with more recent immigrant enclaves overlapping at their boundaries. Where the Dataran is preserved in all its colonial glory, the spaces around it are more dynamic and adept to change.

The inverted city

The Nolli technique of mapping is a reduced representation of the city, which highlights urban spaces by presenting them as voids defined by the solids of the buildings and other structures. Hence, the composition of the urban space is made explicit by leaving it bare instead of highlighting it with a thick marker. Up until 1748 when Giambattista Nolli created his surveying technique to represent the city of Rome, city plans were mostly presented as birdseye perspectives, a more cluttered form that did not always show the structure of the urban space clearly. The reduced representation coupled with the direct angle from above is more revealing.

What if we applied the analogy of the Nolli Map to street protests? This is now easier to illustrate with the use of drones to monitor protests, just as was done at Bersih 4. If we substitute the building footprint with the actual footfall of people in the streets, the location of bodies in space then becomes the structural element of space – the collection of solids which define the voids. The street events, including protests, become an exercise of inverting the city where the building density is transferred into the streets. The high number of people moving together through the streets makes visible the exasperations that have been circulating in the discursive spaces of coffee shops and the media; a visual statement that the power wielded by the authorities derives from the people. The empty Dataran Merdeka in this instance represents a vacuum of trust in the authorities, or on a more positive note, just like the voids of the Nolli map, the potentials of public space.

Therefore the empty Dataran, a symbolic space prepped for the state-sanctioned spectacle, stood in stark contrast with the spaces of everyday life, full of people performing their democratic right of dissent. On some level, this could be read as the public turning its back on the the authorities’ official narrative, in refusing to contest the national symbolic space. Claiming a banal piece of infrastructure and ignoring the more elaborate symbolic space presents the potential of the public to create a new representational space over the one established by the authorities. This process of inverting the city is also an act of defiance, which ironically started with the intention of complying with the demands of the authorities.

Notes on mapping

In mapping protests, especially when they are spread out over a period of time in a space of everyday life, we should also consider the temporal aspect of people going to and leaving the protest. This makes the spatial demarcation of the protest almost impossible, in contrast to protests in more defined symbolic spaces. Protests in such spaces may have barricades around the protestors, or entrances to the urban space, or a live fence of bodies forming a tight mass in urban space (usually in the shape of a circle). In the case of Bersih 4, however, the barricades were around the Dataran, and the protesters were outside of the barricade, not bounded by any spatial constraints, free to come and go as they pleased. It was therefore interesting to observe how the protesters situated themselves in the streets. Groups of people engaged in activism workshops or sharing sessions made way for smaller groups of people huddled together to settle in for the night, and the crowd continued thinning out further from the centre of action. The edges of the crowd were extremely permeable, since there were no barricades, structures or even police barriers demarcating the space of protest.

That lack of a demarcation of the protest space, and the constant flow of people coming and going, made estimating the crowd size rather challenging. Although the organizers stated their intention that Bersih 4 would take place over the course of 34 hours, they also did not specify how long the protesters should maintain a constant presence at the protest site. The size of the crowd was in constant flux during the two days of protest, and as can be expected the estimates offered by both organizers (500,000 at peak) and the authorities (50,000 at the most) varied wildly.

The ephemeral city

To a certain extent, the Nolli map analogy illustrates the potential of street protests as a form of urbanism. That is, city-making by the citizens, as bodies autonomously coming together create fluid new spaces in contrast with the more permanent structures installed by politicians and experts who decide the form of the city. Although ephemeral in nature, such acts of protest may affect the urban space in creating new long lasting meanings and icons, perceived differently by the public and the authorities. This could potentially translate into changes in the treatment and governance of the space by the authorities, and in how the public utilizes and engages with the space. More importantly, it underscores the point that cities are not there just for labour and consumption;

cities have a civic duty to deliver as the space for people to perform their democratic right to dissent.

If the success of protests was measured by whether their demands were immediately met, then Bersih 4 could be swept aside as another spectacle, an illusion that the voice of the people matters. In this era of next-day deliveries and constant updates on social media, our short attention span requires instant results, and it’s too easy to dismiss peaceful protests as lacking potency among more sensational events. Protest veterans have told me that this particular Bersih rally felt more muted than its predecessors. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possible long-term gain of a rising political awareness among an increasingly depoliticized public, conceived by events constantly occurring in public space. Just as the power structure can be read through symbolisms planted in the urban form, taking to the streets manifests the power of the people.

The author would like to thank Malaysiakini for their generosity in providing the drone photos in this article.

- Bersih 4 was the fourth street rally organized by The Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections – better known as Bersih 2.0. The previous three rallies specifically called for electoral reform, as the name Bersih, which means ‘clean’ in Malay, indicates. ↩

- The 1MDB financial scandal had been brought to light by opposition members of parliament, but only started rocking the nation after the Towers of Secrecy exposé in the New York Times in early 2015. ↩