Rome-based collective Stalker has been exploring the neglected areas of the Italian capital and engaging with their marginalized populations for more than 20 years. Stalker co-founder Lorenzo Romito reflects on the group’s evolution and future plans.

CA: Can you briefly explain what your practice is about?

LR: I am one of the founders of Stalker, a collective that explores spatial transformations, engages in observing and promoting diverse participatory, bottom up processes – usually, but not exclusively – in segregated or marginalized communities. It has also been the place and modality of my personal research where I am trying to understand whether spatial processes produced by perfomative activities could contribute in a positive way to urban design that currently suffers from lack of perspective. My current goal is to develop an educational project based on the research we have been carrying out for the last 20 years. I think it will very useful and timely, at a moment when architecture lacks references, and experiences the collapse of the architectural star system.

CA: What kind of projects are you working on now?

LR: We are currently walking through Italy’s abandoned places, or actual territories as we call them. Through the process of walking we are becoming conscious of its cities and making an effort to build a new system of representing these places. The encounters between outsiders and local inhabitants that happen along the way allow for reciprocal learning. It is very interesting to observe how the inhabitants relate to the territory, urban landscape and the environment, and to rethink the role of the traveller in the cultural development of a territory. During the Eighteenth century travelling in Italy was a system of exchange, encounter and cultural production that later gradually transformed into the polluting system of contemporary mass tourism. Tourism is a part of a phenomenon that Stalker sees as the opposite of the actual territory, which we call the contemporary. Our idea of the Twenty-First century Grand Tour1 is to emerge from the contemporary and investigate what exists beyond the collapsing image of today’s architecture.

CA: Can you elaborate on your idea of the actual territory? How do you use this term?

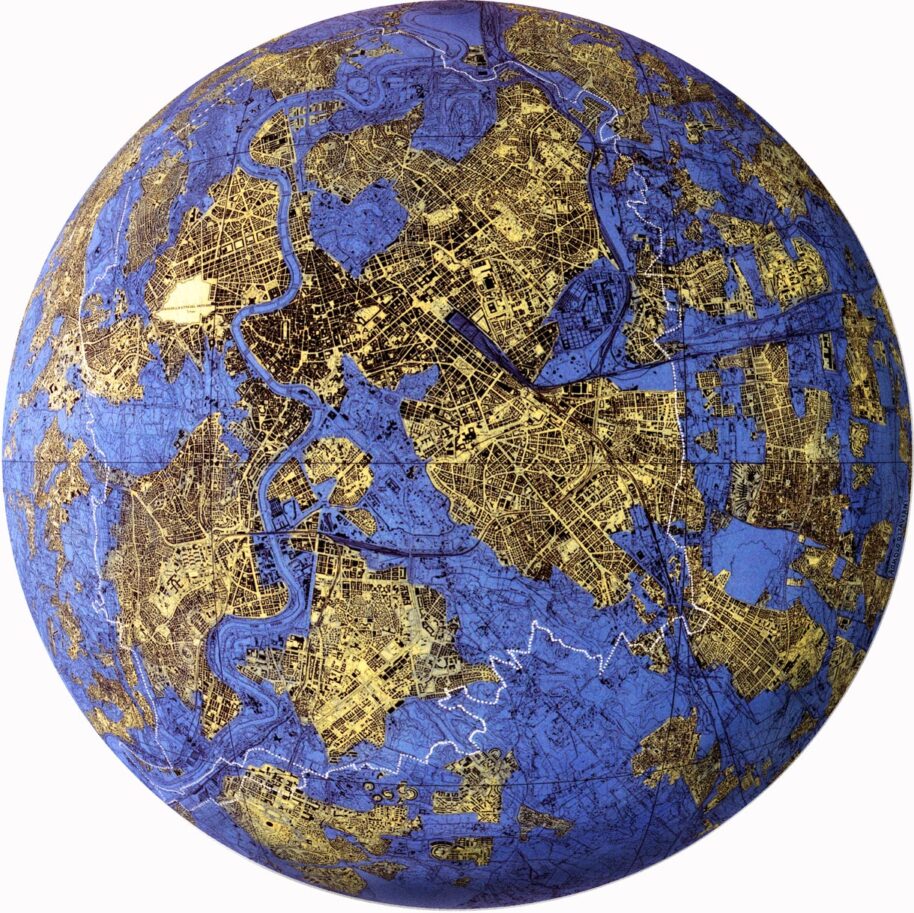

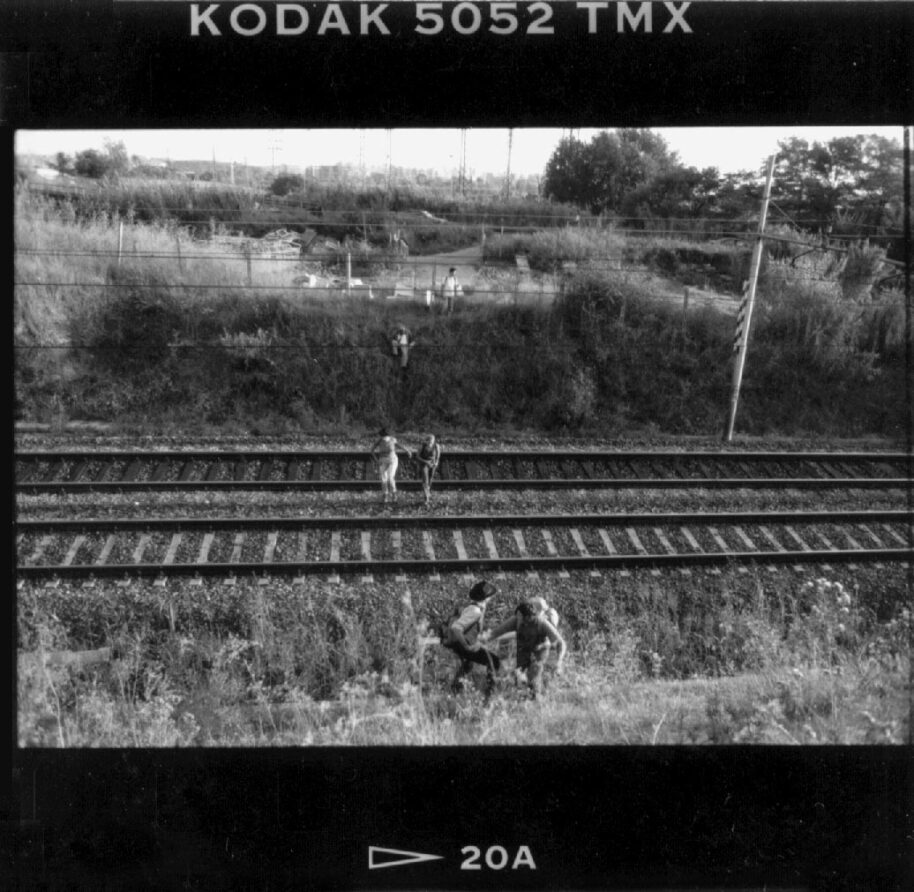

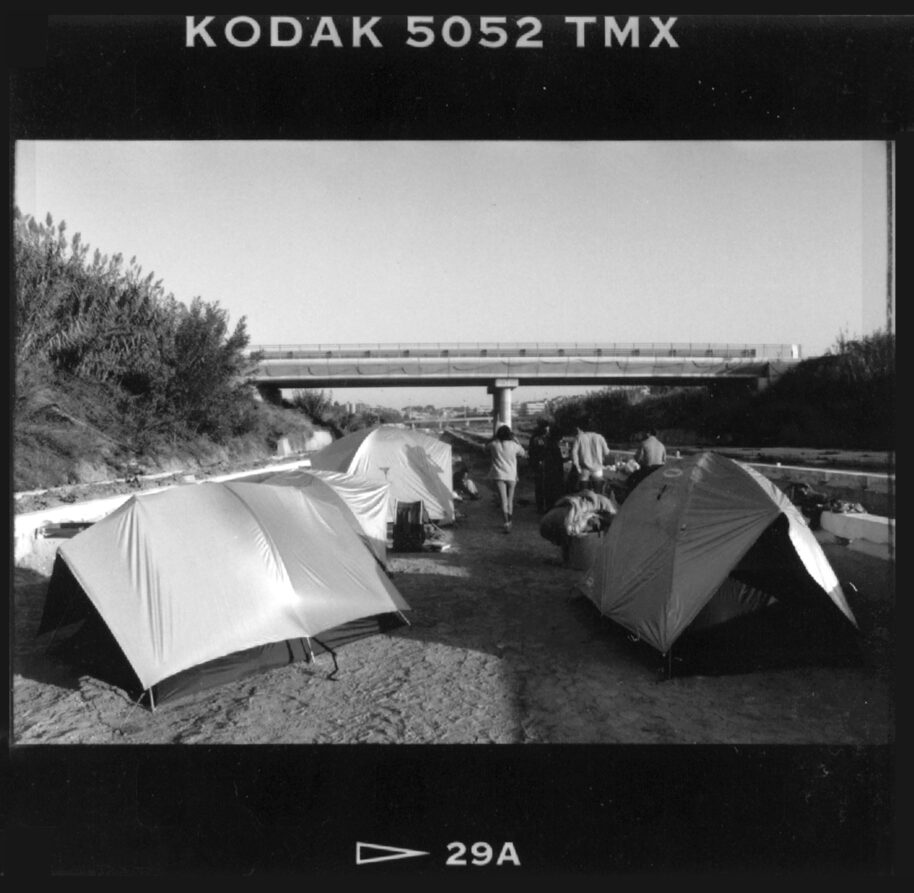

LR: Actual territory is a term we assigned to the abandoned, unknown, excluded and inaccessible areas of Rome during our first exploration in 1995. We noticed that the expanding formal city gradually swallowed diverse territories that used to form an archipelago. Our first manifesto that resulted from this walk defined the actual as the space of the everyday and the dark side of formal reality, which includes all the forgotten, abandoned and marginalized. We want to exclude these spaces in a positive way, to preserve them. During our first five day walk to the outskirts of Rome we considered the spaces we approached to be nomadic and creative from which we could learn a lot. The spaces have been developing through a number of intermingled spontaneous processes; those natural, processes of a productive city and people who were excluded from the city. The contemporary city is a sprinkle of banal, labelled, thematic and self-referential apparatuses alienated from the context. Our idea is to trespass the boundaries between the actual and the contemporary city and create chances of relinking these different parts of the city.

For the last 20 years Stalker has been fighting against the attempt to make everything contemporary and cancel the other dimensions that we study. We think most intriguing sociocultural urban processes take place in the informal, spontaneous and marginalized world – in the lack of control, the weakness of the institutions and the operational capabilities of planning, in the opposite of the hurricane of neoliberalism and controlled urban pop-ups – that seem to happen without a reason. We are trying to understand what is important to the people who inhabit the actual spaces, because we see it as the only way to co-create and cooperate in the transformation of those marginal territories.

CA: Walking offers a different speed through which one can look at things. How did you come to using walking as a form of urban exploration and as a form of urban activism, how does it relate to the other tools you are using?

LR: Walking is a way to locate oneself in the space. It reconnects time and space in a singular and proportional way; it means that one is fundamentally somewhere. Walking is also an experience of freedom. It is an aesthetic and political experience, a moment of investigation and observation of reality by being a part of it. If you are just walking around, it means you are perhaps not really living the moment, but at least you are not sedentary. You are active, ready to play a role in that space. Furthermore walking gives you a perception of what is going on around you and one should make oneself available to be affected by this experience, to learn from it. The perception of space should be fully referenced by the individual experience of it, but also remain open to the creation of a common perspective.

We always try to engage people who have a direct relationship with a certain space in a collective production of its alternative imagination. So our work is not only about walking, but also about being in a place for a while. Especially when it comes to the marginal areas and abandoned spaces that tend to be inhospitable. We want to understand how they can become a part of the living experience and what we can learn from them.

CA: Can you give us some examples from specific projects?

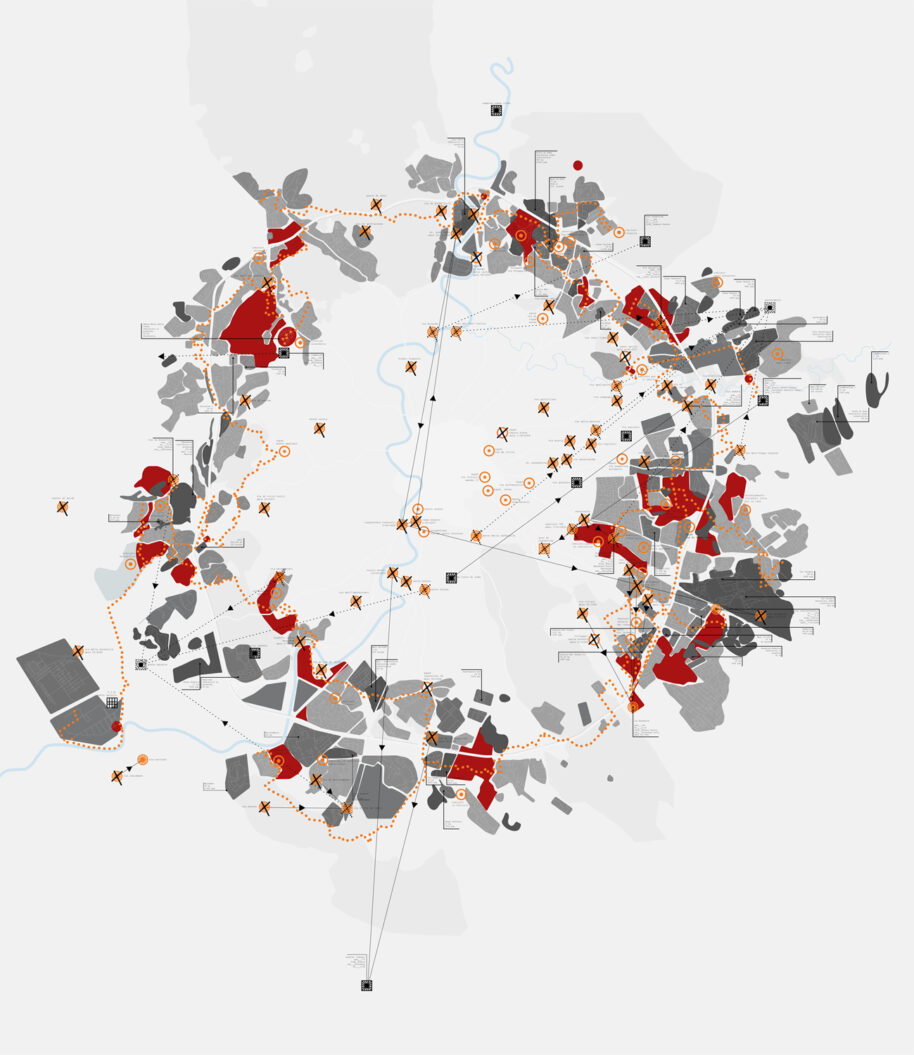

LR: Stalker is mostly known for its walks in Rome, which has always been the core place of our activity. For the last 10 years we have been working a lot with the inhabitants of the social housing block in Corviale.2 Five years before that we shared an abandoned slaughterhouse in Rome with Gypsies and Kurdish refugees inviting other citizens, artists, researchers to collectively inhabit the space. We have been organizing walks in Rome with Primavera Romana Collective to create a map of various social centres which practice bottom up such as: self organized groups, associations, squats, Gypsy communities, refugees, community gardens and alike. We walked along Via Egnatia,3 an ancient road leading from Rome to Istanbul. In the last century, the traces of Via Egnatia have been the route of a dramatic displacement of populations, seeking their way to Western Europe, our goal therefore was to build a dislocated monument to the memory of those who were forced to leave their home place. That was perhaps our most ambitious project because we moved back and forth along the Mediterranean.

There is a growing concern with self-organization among citizens and practitioners, but I also see that this concern creates a vision of a world to share. What I do not see, however, is the emergence of new politics of creation. Even though it seems to sprout every now and again, it immediately disappears. My idea is that this could partly be caused by our disconnection from the territory. That is why our work is emphasizing the idea that the experience has to happen on site. Maybe that is why we do not care so much about communicating our work, it is the experience that matters for us, not the spectacular visibility.

CA: Indeed, it has been very hard to find information about your practice online. Apart from fragmented and scattered mentions; there is not one place where we can actually source your work from. Is that a conscious strategy?

LR: We firmly believe that we cannot communicate our method without sharing the practice, the experience and the action, which are related to a specific territory. We think it is just more useful to be present. Communication forces you to simplify, to target an audience and to accept the contemporary ways of representation, which I find rather lazy. During our public walks, we always leave the ways of representation open: some participants sketch or draw, some write, some take videos and a lot of people take pictures. We just aggregate them on blog pages. So we might not be so evidently present online but our work has very important intensive local presence and is not widely diffused.

CA: If you were try to fully represent and recapitulate the 20 years of your work and therefore were to formalize your working methods, would they inevitably become disciplinary?

LR: The discipline is a part of the process, I am well aware of this risk. Nowadays everybody walks, everybody wants to walk or is starting to walk – walking is becoming part of the contemporary. I see a lot of marketing techniques that aim to transform walking into an artistic practice. I find it scary because that is such an important part of our practice and it feels irresponsible to let someone else handle the representation of it.

AM: Why do you find it scary to consider walking as an artistic practice?

LR: The technical approach involved in the artistic practice cancels the possibility of walking as an open experience. One has to be open to the place one investigates: open to cross a wall, to enter an abandoned place and to what may happen there. Any predetermined strategy is disciplinary and compromises the experience. Of course it can still be interesting as an exercise but when simplified, the potential of walking to take down the walls blocking a possible change is lost.

We are surrounded by pop-ups disconnected from the context,4 I call them the islands of the contemporary. They are artworks, urban spaces or architectures where the lack of comprehension of what is going on in the world defines the possibility of change within them. This is why there is no future beyond the contemporary; present has become perennial; it means that everything constantly becomes spectacular and speculative in order to last.

CA: Would you say that the contemporary, as an all-encompassing device that transforms everything into a spectacle is the main urban issue today? Are you optimistic about things changing in the future?

LR: Am I optimistic? Well… I always feel optimistic, but nowadays we really have to get serious. We have to be happy even if we are not optimistic. But let’s say I am optimistic. The biggest problem today is indeed the contemporary. It is a broad problem, also connected to the touristification of cities. Contemporary architecture has been characterized by selfishness and extravagant expensiveness. Its high costs have indebted municipalities and public administrations. This financial strategy gaining popularity among architects created a condition that exploits the public, citizenship and its rights.

Currently we are experimenting with new ways of taking care of space, by creating social networking, re-inhabiting abandoned spaces, re-activating agriculture or sharing property, food and mobility. These are two competing worlds and it’s difficult to find ways to get beyond them.

Can you see anyone really optimistic that can tell where all this is going to lead?

I don’t.

AM: Do you think the confrontation between these two worlds is leading to an inevitable clash or is there a possibility of a compromise?

LR: I see the clash around us. Look what is happening in the Middle East, in the Ukraine, on the borders of Europe. These conflicts are leading nowhere at the moment. At the same time institutions are not capable of accepting informal practices in an operational way. The State is not very good in giving space to citizen practices. Citizen practices on the other hand become antagonizing or moralistic, which does not produce anything but frustration. Of course we have to criticize the State, but I think the system is so ridiculous that we should not have to take it seriously in the moral sense. We shouldn’t seriously say: ‘what you are doing is so bad!’, because it is evident. We can almost laugh at it!

Maybe we would be more successful at engaging people by laughing.

AM: You said a lot of critical things about architects. Can the architects who played a certain role in making cities up until now catch up with the upcoming changes, how will their role change in the future?

LR: Firstly, they can learn to understand what is going on, which is very complicated, because it involves a lot of chaotic processes. They can learn ways to react and survive from emerging social practices. Their role in essence will be to bring back the question of actual space, becoming engaged, opening up fields of investigation, starting processes of cooperation, instigating collective ways of elaborating strategies and linking specialists and inhabitants in processes that are not typical of western chauvinistic design projects. Design is a process of creation, but it has to be open and it seems that architects have hard time with that.

CA: Would you say that somebody has succeeded in this so far? Somebody you find inspiring, from whom you have learned and would consider him or her your master?

LR: I almost didn’t have access to the generation that still had masters. But of course I had my masters, they taught me how to create possibilities for social change, how to really make people participate in the process of change and how important this is. If you ask about masters, Danilo Dolci is definitely one of them, even though I didn’t have a chance to learn from him in real life. He did incredible work in Sicily during the 1950s and 1960s. In several villages he created schools to educate peasants and fishermen to become planners and engaged them in the creation of the plan for the region. It is such inspiring work. Few years ago, we walked the way Danilo Dolci walked together with the inhabitants of those villages to Palermo. It was a fantastic experience!

The system always resists change, it is evident, but as in the case of Dolci we have to create possibilities for experimentation, because if we remain confrontational we might face a situation where nothing can be done and I think this perspective will become frustrating, produce moralism, lack of desire, pleasure and imagination.

CA: How does all this impact your personal life?

LR: The truth is that I try not to be dependent on the system; we focus more on a set of local relationships that allow us to survive. Of course being invisible is frustrating, but this has been the motivation to turn Stalker’s experience into a cultural and educational action. We want to preserve the quality of our space because we want to live well. I would like to live in a world of relations, where living and travelling is not dependent on a series of regulations that are required nowadays.

We have to aim to create a different world and I try to maintain confidence in that possibility.

On one hand we have to preserve the culture and on the other give it a future and keep it from becoming informational. It is a very tricky moment, because banality is taking over. I think we need the encounter with physical spaces now more than ever. We should all be able to explore possible change with no hypocrisy. If we are not open to life, adventure and love, what is left becomes very boring and the battle is lost. Even if we are still not able to fully express what we are fighting for, it is our social responsibility to try.

- The Grand Tour was a 17th and 18th century custom of a long trip, usually undertaken by northern European noblemen through France to Rome, in order to study the antiquities, culture and arts, and learn about origins of European civilization. ↩

- More information on the Corviale housing complex. ↩

- The Via Egnatia was a Roman road constructed in the 2nd century BC, to connect the two capitals of the Roman Empire, Rome and Constantinople. It traversed through contemporary Albania, FYROM, Greece and Turkey and has remained an important connection ever since. ↩

- In his contribution to Amateur Cities, Bringing the Jungle to the City, Brett Scott also talks about the illusion of access in an urban environment dominated by interfaces that keep us separated from the reality of production, nature and from each other. ↩