We spoke about debt and imagination to Steyn Bergs and Cassie Thornton during Moneylab #3 – Failing Better? in two separate conversations, addressing a set of the same questions from two different perspectives. The final format of this interview as a conversation has a comparative purpose and should not be read as an actual record of a conversation.

CA: Could you introduce yourselves and tell us something about your work and interests?

CT: I’m Cassie Thornton, and my activism and artwork is about revealing debt and economics as forces behind public behaviour and affect. Debt creates circumstances for more work, more avoidance, more guilt – all obstacles to collective dreaming or organizing. Where I am from in the US, many people live in fear of state and federal government systems that do not have their best interest in mind. Instead, our municipal, state, and national governments make ‘rational’ social decisions based on balancing illegitimate debts instead of caring for people’s lives. One example is in a city such as Ferguson, Missouri, one municipality among many that designs its city budget to be largely funded by police department revenue. This means that there are new micro-laws being designed every year to fine people for supposedly breaking laws while walking on the street or standing in their yard. And as may be obvious, these laws impact people of colour most, as do many forms of predatory debt. Though the state acts like it hates you (the Royal You, meaning all people who are not rich), most people continue to work their entire lives to contend with a heavy load of personal debt for housing, education and healthcare costs. In the end, I find that debt has control of many people’s waking and sleeping dreams. How can you dream of a future when you know that you are just going to struggle to participate in reality and then work to pay it off? Coming from a working class family, I was hyper aware of my family and friends’ deep faith and participation in financial and governmental rules and structures that served to centre life around work, discipline and fear of mysterious consequences. That’s why in my work I try to expand awareness of debt as a political issue and, at the same time, offer strange and unexpected opportunities to make contact with imagination.

SB: My name is Steyn Bergs. I’m a researcher, writer and art critic. My background is in art history, but my current focus is on contemporary and digital art. My PhD research at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam is about the commodification, value and reproduction of digital artworks. I’m looking at how their commodification and the ways in which these works acquire value relate to and affect their reproduction and distribution both inside and outside of institutional art contexts.

AM: In Cassie’s presentation in the ‘Global Finance: Failing Better?’ panel we saw how perception of value can change in relation to age. Have you noticed any similar shifts based on other criteria?

SB: Well, the obvious and perhaps the main one is of course class and economic position, at least when we consider value in a strictly economic sense. Cassie’s presentation focused on debt, and naturally being in debt or not strongly affects how you perceive value.

CT: What I’ve learnt through my work is that people who have a lot of money still live with a feeling of scarcity, and people I have met for my projects have confessed that they spend plenty of expensive time and energy working to protect themselves from loss. Of course they are cautious not to risk losing their social and capital assets, but the protectiveness the wealthy perform is a full time job. And among the rich I have worked with, shame, isolation and the feeling of failure are common effects of living with the pressure to prove their own value against the grandiose expectations and powers we project on money. But here’s the kicker – those very same feelings of shame, isolation and failure are the exact descriptions of how people feel who are financially indebted.

This makes me think: what would it mean to succeed, to be good enough? How does one prove your personal value when the metrics are based on money, and money doesn’t ‘work’? Self-worth is based on a sense of hyper-individualized productivity.

Especially among educated people there’s a desperate need to prove ourselves, and I think it directly relates to the fact that we’ve had money invested in us, which is judged to be wrong in a time of austerity when the mainstream idea is scarcity, and no one should be given anything nice.

Being an adult includes some sort of yearning to be more than you are. Children are so brilliant, because they have a sense of pragmatism and honesty about their needs, and they ask for help in order to get their needs met; while having needs makes many adults quiver under a table until there is an app to help. I think that adults are jealous of kids for this reason.

CA: In your presentation you mentioned that imagination is vital in order to not get stuck in the current financial cycle. How important is art or other types of visualization in making abstract concepts such as debt tangible for people?

CT: I’m not sure anymore. I think that a lot of people are not able to talk about money, finance or value, because they see them as abstract and coded matters that are unfit for polite society. People should be able to speak about these notions as human experiences as well as common political issues, and I don’t think that art is critical in this process – but imagination is! Throughout different discussions at Moneylab #3, people brought up the idea of abolishing the artist and advocated spreading imagination into everyday life. I feel that this is my job!

SB: There are different ways in which art, artistic practice and culture in general can create awareness of the abstract nature of money. Artworks I appreciate often succeed in making the grandiose and abstract notions of finance, global economy or capitalism tangible on a subjective level. This brings awareness of one’s position in the system. In some cases it also leads to a better understanding of your degree of agency – that you are not completely powerless, and that certain things can change. The strategies artists use to achieve this can be extremely diverse, and that’s a good thing.

CT: To me visualization and hypnosis are really important, because they allow me to work with one person at a time and have them look closely at things that they feel, even if they lack the language to describe them. These methods allow me to work with people to find a new language to understand the things they find impossible in their lives. I believe that when one person has achieved that, they can spread it to their friends and families.

AM: Is there a certain amount of imagination, or a degree of repetition in the practice of imagination needed to free ourselves from the ties of the accepted narration?

SB: I don’t think there is a point in talking about how much imagination is needed in quantitative terms. Drastic change will not come from artistic practice. It is dependent on many more factors.

What art can do is to facilitate the space for being and remaining critical, for thinking about other scenarios, enacting them, experimenting with different ways of relating to one another and of living together.

Whether this will become reality or reality will just continue to become more and more dystopian, this is impossible to predict.

AM: Steyn, in your presentation in the ‘When Art Mirrors Marx’ panel, you mentioned an interesting example that belonged more to an activist than the artistic domain, where the artistic representation of the project was almost a by-product. Are there other examples of collective practice that can help push the limits of radical imagination?

SB: A lot of practices today connect to different fields and don’t aim to be autonomous – they often connect to social struggle, political activism or political action, and they can still be distinctly artistic. In the particular example of Adelita Husni-Bey’s ‘White Paper: The Law’ some would say that it is all about the activist component of the work and that its ‘art’ character is a by-product, but because her work is recognizable as art (and I think it is for sure, precisely because it contains a component of radical imagination), the project can enjoy the protection of the artistic sphere and – importantly – could be realized thanks to the funding granted to Casco, the institution that conceived of the project with Husni-Bey.

CT: I think it’s really important to talk about finance in a very straightforward way. I usually ask people to tell me what their relationship to money is: what’s it been like to borrow, what it’s like to lend, when do they feel like they’ve been screwed over, when do they feel like they’ve experienced generosity? From there I want to understand how these experiences inform who they are and what they’re doing. Everybody’s financial story is his or her life story, but nobody really tells it that way.

People believe finance and debt construct a reality that is inescapable, but simply by asking questions, it is possible to give them a number of tools that open up new ways of thinking.

AM: Can you imagine something like this, but then on a collective level? Group therapy on radical imagination for society as a whole…

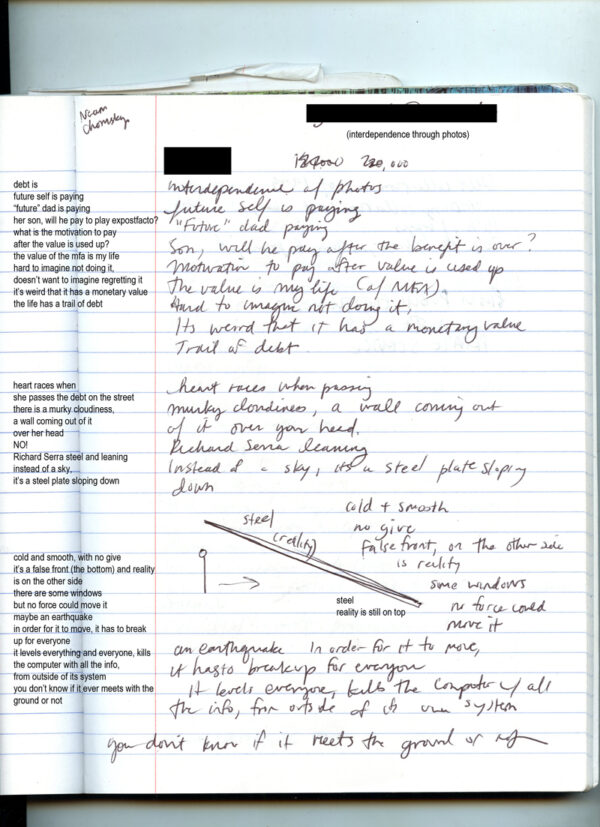

CT: I’ve been doing debt visualization with groups of people for many years. Usually we find that there are common patterns in what people see when they imagine what debt looks like. I’ve also experimented with other forms of collective visualization, such as projects where we make dance movements based on these images of debt, draw them or make sounds out of them. I think that visualization is an amazing practice for letting one person into another person’s mind and allowing them to not be there alone, sometimes for the first time.

On other occasions I had individual debt visualizations with different people around collective debts. In a project with Chicago Public Schools, I interviewed many people about a debt that they were experiencing and visualized it with them. The objective is to get people to talk deeply about an invisible shared experience. This enables people to see themselves as a part of a collective, and what kind of potential power they have that way. I’m just beginning to imagine how to develop a citizen debt audit for children to actually audit the Chicago Public Schools. This would be a step towards a collective radical practice.

CA: Steyn, you said in your presentation that there are still lessons to be learnt from Marx. Which lessons would you like to explain to children?

SB: There are plenty, I guess. I really liked what Cassie showed about how one is forced to grow to think in economic terms and manage one’s life as an accountant. This thinking is prevalent, and that’s the one that Marx was opposing. So what we could teach children, for example, is that you cannot eat money, or that there is no use in money, but I guess they already understand all of this better than most of us adults.

AM: You both brought up commodification of the public education system, living and art. Do you think there is a limit to what can be commodified?

SB: That is a very good question. The optimist in me would say yes, but what we actually see today, which was very well exemplified with Jeroen van Loon’s Cellout.me project, is that the domain of what can be commodified is still expanding. Interactions are commodified through social media – in Jeroen’s case genetic material was commodified; copyrights and patents fall in that domain too. So, even though I would like to say, yes, there is a clear limit to what we, as people, can take, I really don’t know if that’s true.

CT: It’s really scary because everything seems to fall in an avalanche of privatization and financialization. The fact that people see, at least in the US, that nothing is public anymore pushes them into defensive mode. I see a real danger in that because the more people are self-defensive, the less they are demanding social goods. I think more can and will still become privatized and commodified, and that’s really sad, but there are also amazing things happening on the opposite side. Take for example the Dakota Pipeline protests. It’s really unimaginable that US citizens would recognize themselves as a part of the land and want to protect it. We’re so financialized, we believe that only our own individual bodies are what we can protect. In recent US history, there’s no connection between an individual and the land, so I feel like we are at some crazy turning point.

CA: What about art? Can we preserve the value of an artwork, recognize it as such and still resist its commodification?

SB: On the one hand, there are contemporary zombie-formalist artists whose works go straight to auction houses, are sold for record prices, get stored in free ports and usually make headlines. These artworks, much as I despise them and think they are poor, are interesting to me as theoretical objects, because they so ostensibly only have exchange value and no use value. On the other hand, with regard to art escaping commodification, there are numerous ways in which artists today are addressing this question. Artworks that cannot be sold are often seen in performance or in social practice. Of course there are always compromises; artists need daily money, they need to pay their bills and sustain their practice. This means that they often have to do other jobs or compete in the market for public arts funding (at least here in Europe). But still, there are various ways in which they are escaping and resisting commodification. This doesn’t necessarily make it easier for them. Quite the contrary, but (unsurprisingly) it’s also these people who have the kind of practice that is interesting and relevant today.

CT: In the US there is no appreciation for intellectual or creative work; making money is the way to prove one’s value. Rarely do artists have the ability to take the time to focus on something long enough to really understand and comment extensively on it. There is always pressure to produce as much as you can, as fast as possible.

If art can’t stop time, and push finance out of its face to actually see what’s happening, it becomes like everything else…

I’ve done a lot of work about art as a by-product of debt. People in debt often fear that their future is at stake and become obsessed with it. The art they do is a reflection of their state of mind, and in that sense art becomes a by-product of the debt that the person is in. I always thought that the white cubes that were assigned to us at art school – to live in and produce work, alone and separated from the world – represented a highly pacifying and also dysfunctional system. Surprisingly, an inescapable white cube is the most common imagining of debt that people describe to me. It’s a huge joke that artists who are supposed to be free and operate outside the constraints of reality are actually the ones living inside those cubes. Luckily, a lot of art happens outside of the art world, and it’s super interesting.

AM: Could the ability to destroy something – as in Cassie’s ‘Mystery Hands’ example – help liberate us from a cycle of constant creation?

SB: Cassie’s example is destructive in the sense that walls are being torn down, but something is also produced there. It’s not material; it’s not a text or a clear end product but a shared moment, a form of consciousness or a critical insight, so there is both production and destruction.

CT: What I’ve devised for my own survival, when I feel stuck in that momentum, is to imagine dead people. It makes me realize that the walls of reality are much more permeable than those we live in day-to-day. Imagining that dead people exist, existed, and will exist after me, takes the pressure off. It makes me feel that I’m a part of a continuum. I might be working on a project that began way before I was born, and it might not be finished until way after I’m dead. Whatever I’m doing is worthwhile in a way that I can’t really understand.

The freedom of the artist is to actually stop time, look at the constraining forces and try to understand them. Ultimately, art can be an amazing form of destruction. Children naturally want to destroy things, but it’s not necessarily only violent. It’s mixed with creativity and collaboration, an amazing thing that adults tend to contain. It feels really scary to unleash real violence, but collaboration and creativity are violent as well. We should definitely start a demolition company for children!

This interview with Steyn Bergs and Cassie Thornton is part of the Amateur Cities collaboration with the Institute of Network Cultures for Moneylab #3 – Failing Better.