Lea Schönfelder designs what she calls games for adults. They are meant to motivate her players to reflect on the paradoxes of contemporary life, their ethical choices and politics of the everyday life.

CA: You have an artistic background but you are currently involved in diverse activities around games; can you briefly explain your work?

LS: Indeed I am an animator and artist, but mainly I am a game designer. I’ve worked on many independent games and personal projects. I’ve worked for a free2play company that produces games for mobile devices and I am currently based in London where I work as game designer for Ustwo Games. I also do a lot of other things in the games field, for example I’m a jury member at festivals, curator and occasionally I teach or write about games.

CA: You call your games ‘games for adults’. What does that mean?

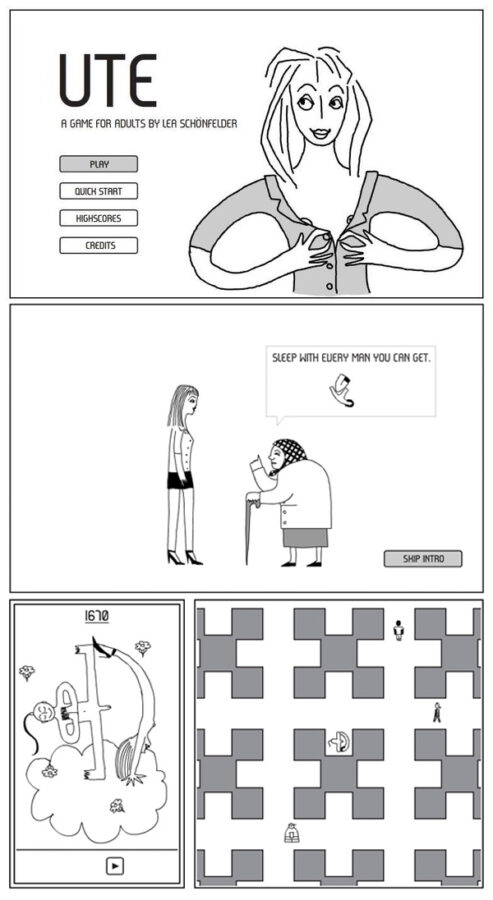

LS: Games for adults is a phrase I came up with when I made the game ‘Ute’. ‘Ute’ is a game about a woman who tries to have as much sex as she can before getting married. I used the term ‘game for adults’ because obviously it’s not a kids’ game, so I didn’t want children to play it but I didn’t want to sound too restrictive either, because it’s not a violent game. Additionally, games are often seen as pure entertainment; many people do not recognize them as a form of art, they think that they cannot learn from games. Particularly, many parents fear that their children lose their time by playing a lot while they should be studying instead. Concerns like these are valid for many games but not for all of them. Games as a medium can be used with many possible goals other than entertainment. I make ‘games for adults’ about serious topics, which raise questions on social practices, politics and culture.

CA: Can you give me some examples? You mentioned ‘Ute’; what are other projects that you have developed?

LS: Another project – ‘Ulitsa Dimitrova’ is a game where you play a seven-year-old kid living in the streets of St. Petersburg in Russia. It is actually based on a true story. My brother used to work with street children in St. Petersburg and he used to tell me a lot about their life. Piotr is a nice character, so as a player you can easily identify with him and have fun but the story always ends very sad, because he dies when you stop playing. The player faces a rough reality when walking through the streets. Even Piotr, despite his seven years of age is already a chain smoker, steals stuff and trades it for cigarettes on the black market.

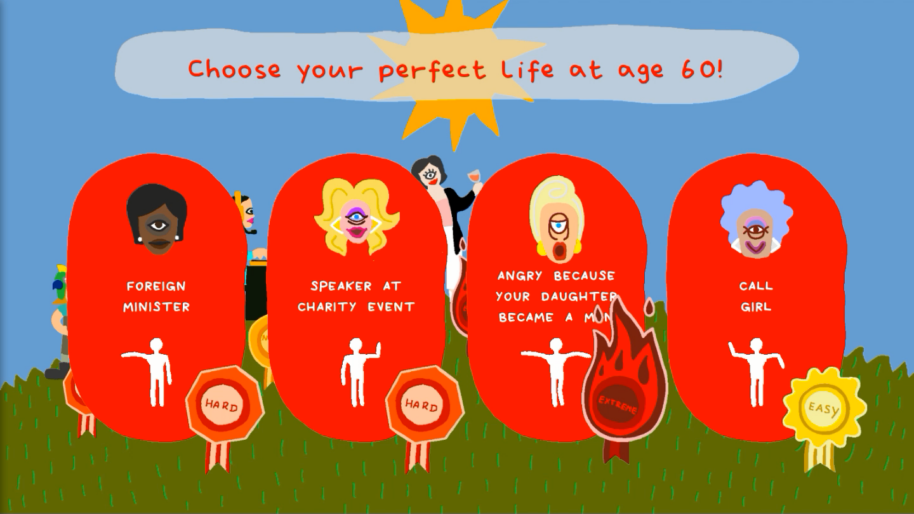

A recent game of mine is ‘Perfect Woman’, which is about perfectionism perceived as a role model for women. In older times, the perfect woman needed to have mainly cooking skills and to care for the kids, but nowadays that’s not enough. On top of everything that was necessary in the past, women now also have to be successful, rich, pretty, athletic, have good friends and more. In a perfect life, you should have all of that at once and ‘Perfect Woman’ deals with how difficult that actually is and maybe not really necessary in order to be happy.

CA: What motivated you to start working with games?

LS: Originally I landed in games coincidentally. I studied illustration and animation and by chance I got involved in some attractive game projects with other students. From then on, I kept working on games because I found rule sets a good way to express myself.

I prefer to create a system rather than a linear story.

CA: Are there particular topics that you find inspiring in you in your work?

LS: It’s mainly everyday life actually. It doesn’t have to be big feelings or important things. I am interested in little moral conflicts or questions that we face during our lives.

CA: Do you think that games can really make a difference in the ways people deal with serious social issues?

LS: Yes. I do think so. I don’t think that games are more powerful than other media. A book, good painting, dance piece or other expressive medium can all change your way of thinking, and games do it in their very own way. There are some famous examples like ‘Papers Please’,1 where the player is a customs officer whose role is to decide who crosses the border and who doesn’t. It takes place in a fictional setting but the player has to face several moral questions, like making decisions that could either have negative effects on someone’s private life or make them a lot of money.

CA: Do you think games are more explicit in the message they communicate, especially when they address the ethics of everyday life?

LS: As I’ve said, I wouldn’t value games as better or worse than other media. I think the power of games is that they make clear that every action has consequences. Because every player interacts with the game in different ways, this can be more or less direct but the bottom line is that when the player gives an input, something comes back, and this relationship between action and feedback is unique for games.

CA: Are there artists whose work you admire?

LS: There are many game artists whom I admire and have learned from, also people who don’t work in games who have inspired me with their style or sensitivity. I appreciate each one of them for a very different reason. For example, I really like the work of Paolo Perechini; he makes satirical, political games. I admire him for his wit. Playing his games almost hurts, but at the same time they are very direct and not much depth and interpretation are necessary. I also admire Eddo Stern, Nina Freeman, and Anna Anthropy. From non game-related fields I am fascinated by the work of animators Andreas Hykade and Ines Christine Geißer.

CA: What do you complain about most in your daily work?

LS: Having the experience of work in both the independent game scene and in a commercial company, I really detest the disregard that both groups have for each other. Artists tend to think that they know better, that they have a superior vision and that wanting to earn money is stupid and evil. On the other hand, what I hate in the games business community is the complete opposite. They think of artists as dreamers and not very good game designers, overestimating their knowledge and craft; I think but they could be more innovative and not as conservative as they sometimes are.

CA: Do you think conservatism is inevitable in a business-driven environment?

LS: I don’t think so actually, but I can think of reasons why it happens – people who work in this environment for a long time get comfortable and don’t want to change everything all the time. But to bring the medium forward, some kind of revolution is necessary in the industry, at least content-wise. That’s not to say that everybody is doing things wrong, but they don’t feel much pressure to think outside of the box, as it is safer to keep following the same principles to earn money.

CA: What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned in your career so far?

LS: I know now how different these two communities are. I always thought I would work in games and that there is a coherent ‘games community’ but actually there is not. The indie games scene and the corporate games scene are very far apart, at least in Germany, and I wish that they would intermingle more.

CA: Do you think that in the future games as a medium will be used more to address serious issues that relate to society or the city?

LS: I hope so! People talk about it a lot and there are efforts being made for this to happen more often. There are many serious games. What I think is hindering their expansion is what I perceive as a struggle faced by serious games developers; they are always asking the question: ‘Should a serious game be fun?’

This fun aspect is, in my opinion, slightly overrated because fun can be so many things, and something informative can be also fun.

Reading the newspaper is fun for me because I learn something new, so I don’t think that information needs to be hidden behind game mechanics that are there just to make it fun. The process of using serious games to address various, social issues is slower than we would have hoped for but it’s definitely there.

CA: What slows it down?

LS: I’m not too involved in the development of serious games for schools but I often hear from teachers that educational programs are still quite inflexible, so as a teacher, you cannot use a game that you find relevant in your classes, because it has to fit to the subject that your students have to learn.

A lot lies in the communication between teachers and game designers, which is currently insufficient. Game designers may not feel the need to make games for this target group and teachers do not always appreciate games made for them. But if teachers don’t find games useful, then why would anybody want to make games for them and the other way around, if there are no games available, why would teachers rethink their opinion about games. It’s a vicious circle.

I hope that the more ‘normal’ games become accepted – and they are, because everybody plays games on their mobiles nowadays – the easier it will become to communicate and adopt games for various purposes. But I also find it important to really include technology – not only the consumption but also the production of software – into education earlier on, at schools and even kindergartens. Of course not everybody has to be looking at a screen constantly, but early exposure could help people become familiar and might even stimulate them to go into this field later.

CA: Do you think that you could apply game principles in real life cities?

LS: As a matter of fact we are designing rules in city building, politics and everything that happens in our communities. There are rules for the kinds of houses we build and how to build them, places to walk and drive; it’s all very similar to game design. It is a little more chaotic and there are more parameters than we can control, so it is probably more difficult than designing a game – if it wasn’t we wouldn’t have any problems; but on a conceptual level there are some overlapping questions.

CA: What are you working on at the moment?

LS: I am working on a game called ‘Growth’, where the player starts as a king or a very rich person and earns a lot of money, owns many buildings, generates resources and is able to buy everything he or she wants, but every time the player spends money everything gets worse and there is no way to improve the condition of the world. The game is intended as a commentary on base builder games2, it is built on a very similar scheme where the player starts, builds and brings his or her kingdom higher and higher, becomes more and more powerful and the question is what for actually? In ‘Growth’ it’s exactly the other way around, but in your downfall you can decide what kind of poor person you want to be.

- Papers, Please: A Dystopian Document Thriller is an award winning puzzle video game created by indie game developer Lucas Pope. Play Papers Please here. ↩

- Base-builder games are based on designing, building, maintaining, and expanding a structure, ranging from micro to macro management. City-building games fall withing this genre. ↩