With the unstable political ground in recent years, the subject of architecture in the political setting has suddenly gained new interest worldwide. As a response to the post-2008 financial recession and its inevitable repercussions within the built environment, the prevailing doctrine of corporate ‘iconic’ architectural production is now being greatly challenged by the daring alternatives from the opposite end of the social spectrum – the local ‘bottom up’, ‘community-led’ architectural actions. What is the potential agency of architectural practice in the field of politics?

Is architecture only a passive reflection1 of current political matters or can it formulate its own claims, demands, agendas and above all, can architecture use the means of activism to critically engage with broader social and political concerns?2 This article is a reflection following a project I have recently developed under the topic of ‘Architecture and Activism’, where I attempt to employ architectural theory and practice as means of engaging with global matters of concern. The island of Diego Garcia became the focal point of my investigation because of its contemporary relevance and turbulent past that has been the subject of continuous political controversy over the past 50 years.

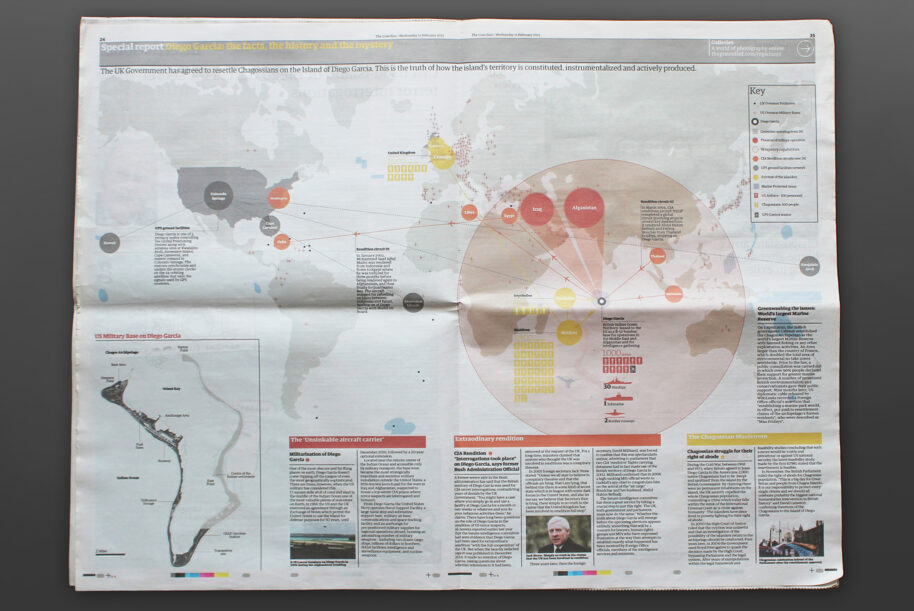

‘Cry my beloved country. Chagossians are still prevented to live on our motherland’ waved up in the air outside Downing Street in May 2015. For already 40 years, indigenous inhabitants of Chagos Archipelago are far away from being home. Situated in the middle of the Indian Ocean, Diego Garcia, the main island of the archipelago, is one of the most remote and inaccessible places on earth. It does not come rolling off the tongue of even the most geographically sophisticated. Yet there were times when the United Kingdom considered this 27 km² of coral and sand one of the most valuable pieces of real estate. In 1966, after the British Government detached the island from Mauritius violating the UN resolution on the dismemberment of colonial territories before independence, this tropical paradise was leased to the American Army. Ever since, Diego Garcia has operated as the biggest US military base outside the United States. With over 20 large cargo ships anchored in its lagoon at any given time, the island is a little-known launch pad for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that the Pentagon characterizes as ‘an indispensable platform for policing the world’. At the same time, over 1,000 American troops and almost 2,500 civilians entertain themselves daily with supporting base facilities such as a windsurfing club, a yacht club, a 9-hole golf course and annual Miss Diego Garcia competition; transforming the territory of the island into just another American town.

For this spatial anomaly to happen, in the 1960s, the UK Government had to secretly expel the whole Chagossian population; committing a crime that falls within the remit of the International Criminal Court as ‘a crime against humanity’. While dozens of jobs on Diego Garcia are advertised every day in Mauritius, the Seychelles and the Philippines, including positions for electricians, janitors and massage therapists, there is not even one Chagossian living or working in their motherland. 40 years after their forced displacement, the majority of the 5,000 exiled Chagossians are still actively campaigning for their right to return. Yet, the government’s manipulations of the legal framework around the case and feasibility studies conclude that such a move would be ‘costly and precarious’ or against US national security, conservation, or global warming and therefore Chagossians are still unable to access their island.

Today, it is crucial that the island is brought back in to the public discourse because at the end of 2016 the 50 year-long US military lease of Diego Garcia will expire and the negotiations for its 20 year extension are currently taking place. In 2015, the UN Tribunal voted that the expulsion is of the islanders was illegal while the latest feasibility study stated that conservation, defense and security are not the obstacles and that the resettlement is feasible. However, in July 2016 the UK Supreme Court ruled that resettlement would be prohibitively expensive.3

Through its lifespan every artifact, ranging in size from a miniature object to the territory of an island, is entangled in a network of social and political relations. There is no neutral piece of material culture. Every fragment of our environment embodies the social or economical system that has created it. Like the configuration of the beautiful grand boulevards in Paris conceived to exercise power over the French rebels of the Nineteenth century, or the unusually low highway overpasses on Long island in New York that have played out against the lower class buses from American suburbia.4 There is no neutral ground for architecture to build upon. By practicing architecture one instantly dilutes from any political and ideological neutrality and intervenes into a network of socio-political relationships that surround his actions. In his writing, French sociologist Bruno Latour announces the shift of critical attention from architecture as a matter of fact to architecture as a matter of concern, where consequences of architectural action are of greater importance than its physical manifestation. However, this does not mean to abandon design per se, but rather to understand the role of an architect more broadly and beyond reacting to the identified spatial problems. In the 1960s, architect Cedric Price was already advocating architecture that challenges the idea of what one builds and why. Architecture that, in the words of Rem Koohlaas, ‘dismantles one by one the most holy ambitions of an unquestioned profession’,5 making it disappear into an unconventional system pertinent to up-to-date social demands. While the Oxford dictionary states that architecture is ‘the art or practice of designing and constructing buildings’, Price seemed to disagree. For him architecture ‘should have little to do with problem solving – rather it should create desirable conditions and opportunities hitherto thought impossible’.6 In this context, the duality of a pro-active architectural practice becomes a valuable resource that has both the ability to expose, formulate and to respond to a socio-spatial problem. If an architectural project is to be understood as a fabric of relationships between places, people, institutions and the state, can architecture act as a form of resistance and intervene in the political condition, for example around the island of Diego Garcia? Can architecture be seen as a political practice?

In 2008, prior to the 11th International Architecture Biennale in Venice, Aaron Betsky invited architectural thinkers and makers to give their response to the selected theme of ‘Out There: Architecture Beyond Building’. He encouraged the participating architects to address the central issues of our society rather than to showcase their most recent work. Betsky pointed out ‘what should be an obvious fact: architecture is not building. Architecture must go beyond buildings because buildings are not enough.’ The same year, Alejandro Aravena’s Chilean office Elemental was awarded with the Biennale’s Silver Lion for a Promising Young Architect. Eight years later, Aravena is the winner of the Pritzker prize and has been appointed director of the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, roles that are often awarded to well-known ‘star architects’. However, he was not selected based on prestigious status, but because of Elemental’s socially responsive work that apart from design also involves processes of working with local people and investigating the budgets of government departments and agencies involved.

Almost at the same time, Assemble, a young London-based architecture collective became the first architecture or design studio to receive the eminent Turner Prize, Britain’s most important art award that is usually granted only to high-profile artists such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin. This young collective won the prize in honour of their Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool, which was developed in collaboration with the residents of this rundown council housing estate where the locals took it upon themselves to paint the buildings, plant new vegetation, create social outdoor spaces and establish a local market. Today, Assemble represents a new generation of young enfant terrible architects that refuse to play the top-down corporate game. Instead, together with other like-minded practices such as Architecture_00, Carl Turner Architects, Public Works, Studio Weave and We Made That, they commit to people’s everyday needs and promote the profession’s civic role. There are two ways of exploiting wood, argued Reyner Banham in his book Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment: to construct a wooden hut or to build a fire.7 This profound collective seems to have chosen to set the fire and made a call for a radical change of the current architectural status quo. In some ways, with their lo-fi solutions and self-build co-operative approach, they seem to mirror the counter-cultural explosion of the 1960s where the ordinary individual was empowered to participate in the architect’s romantic fascination with science and technology. It is still too soon to understand the impact of this emerging movement, however their recognition by the institutions such as the Venice Biennale, Pritzker Prize and Turner Prize, implies that there is a call for a new proactive approach.8

Forensic Architecture, a London-based research agency, is another good example of a spatial practice that challenges the question of architecture in a political setting on a completely different scale. FA uses standard architectural tools and knowledge to articulate contemporary notions of public truth in various legal and political forums. The group employs an operative concept of a critical practice on the scales of bodies, buildings, territories, and their digital representation to investigate the actions of states and corporations, offering their analyses to civil society organizations, NGOs, activist groups, and prosecutors worldwide.9 For this ferociously creative group of architects, artists, filmmakers and theorists, a building is never a static entity. They argue that today, when contemporary conflicts are increasingly taking place within the built environment, buildings have the ability to register external influence, memorize and produce architectural evidence. A process through which the various material components of the building— concrete, steel, plaster or wood— automatically store surrounding conflict forces, and with the help of advanced architectural and media research can further transmit this information. In the latest instalment of the six-part Al Jezeera’s film series ‘Rebel Architecture’, FA founder Eyal Weizman explains how ‘pathologists need to have medical intelligence to understand what happens to a body that was destroyed, we also need to have architectural intelligence to understand the spatial violence’.10 Through the cases that vary from mapping the Guatemalan military’s genocidal campaign against indigenous people back in the 1980s to the analysis of the destruction of buildings targeted by drone strikes in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia and Gaza in more recent years, Forensic Architecture are using means of architecture to challenge the way human rights controversies are investigated.

Keeping these examples in mind, the Chagossian matter can be disclosed and acted upon on three different levels: as a straight one-to-one action, as an architectural response to the scale of the island or as a geo-political intervention into the unique entanglement of military, human rights and environmental stakes that have been established around the island’s territory. Through different scales of observation and their intersections, I have investigated how an architectural intervention could result in a shift in the balance of power that has crystalized in this remote territory and provide support for the resettlement of the exiled community of native inhabitants. By employing a series of live actions – including the organization of public forums, debates and community-led design, my work became part of the Chagossians’ on-going activist campaign to return to the island. It is precisely the agency of activism that expands architecture beyond design; one that deploys strategies, fosters public debates, empowers and mobilizes people and, finally, negotiates change.

Right: Lets talk about architecture through performance – ’Participation say what?’ performance, Royal College of Art (2014) by Lavinia Scaletti and Rosa Rogina with Zarya Vrabcheva, Rodrigo Garcia Gonzalez and Paul Boldeanu.

The territory of Diego Garcia is recognized as a prism, through which a set of contemporary conditions of power and culture can be examined in great resolution. A speculative architectural intervention out there is an attempt to foster debate here and now about the (mis-)use of the discursive apparatus of ‘rights’ – be it their human or environmental rights – as a support to global power structures. Indeed, the island also reflects how climate change and environmental protection arguments are contributing to shaping of its territorial and political condition. In April 2010, the British Government established the world’s largest Marine Reserve Area by banning fishing and other exploitation activities around the island. An area larger than the country of France and more than twice as the size of United Kingdom was later proven to be an environmental blackmail, designed to prevent the native nation from ever returning back.11 Could architecture, in a reversal of the same process, use strategies and legal frameworks of environmental protection to support the claims of the exiled Chagossian community and to act against the island’s occupier? If so, how can an architectural intervention in this scarred military environment act both critically and propositionally in an attempt to bring social and spatial justice back to the island?

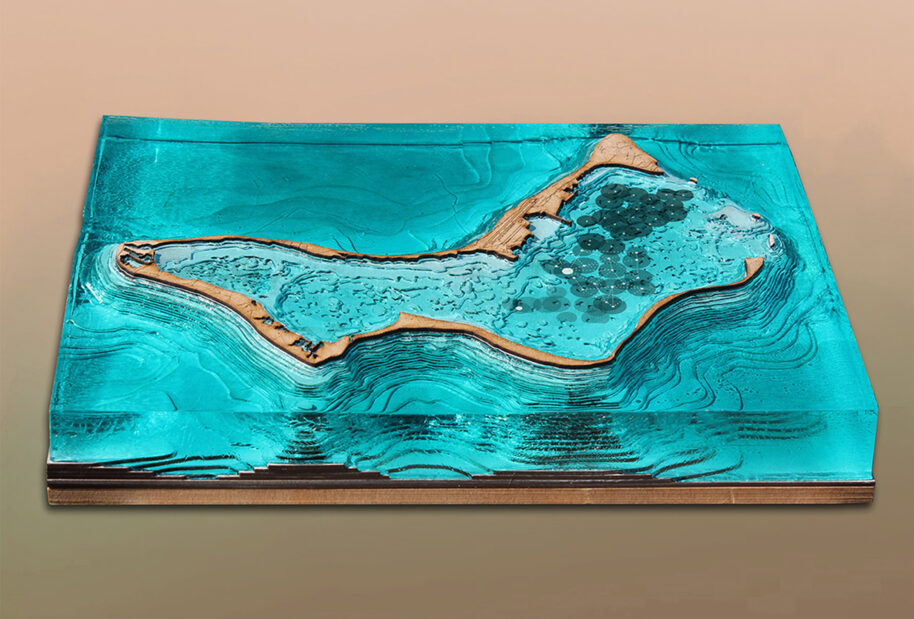

In my personal attempt to answer these questions, the island could be imagined in the event of the resettlement as a territory that would initially be shared between two opposite presences: an occupying army and a community of returning exiles. Where, through a process of reclaiming water and land, a progressive replacement of the former by the latter would happen. However, if the only existing physical remains of a certain territory are solely of a colonial nature, how can one unveil potential of such an out-of-reach place? It is precisely colonial architecture, argues Eyal Weizman12, that was a milestone for using the built environment to exercise political and economic control over the civil society; where the violation already started on the architectural drawing.13 To avoid the reproduction of the colonial schema through architecture that first led to the forced displacement, it is critical not to impose a design solution for the resettled community and to leave the decision of how to re-inhabit the island to them. Instead, the key responsibility of the designer should be their first means of survival – the physical and economical infrastructure that may sustain the resettlement. In the other areas of low-lying coral atolls around the world, one of the most stable economical systems is formed around community-led coral farming that promotes the opportunity for rebirth of coral reefs through the work of local people. In that sense, the Chagossian resettlement has a potential to act as an environmental healer for the scarred military lagoon that lost two thirds of its coral area by processes of military anchoring, dredging and explosions.

Once again, going back to the 1960s, in his probably best-known realized project for the Snowdon Aviary at the London Zoo, Cedric Price used tension cables, point supports and moving joints to enable the movement of the wind to completely alter the structure. Consequentially, this obstacle-free volume manifested what Price believed were dominant functions of architecture: spontaneity, change, joy and delight. As it was designed for a community of birds, Price imagined that once the community was established, the netting would have to be removed. He claimed it was only necessary to be there long enough for the birds to start feeling at home, and was sure once they did, they would not leave anyway. To a great extent, Price accepts change as an essential element of human existence and believes in an architecture that, throughout time, gains from its failures and imperfections. He advocated the principle of ‘calculated uncertainty’, endorsing the creation of indeterminate structures that can be altered, transformed or demolished when socially irrelevant. For Price, the most enjoyable thing about a Blackpool Zoo café he designed in 1970s was not the idea of somebody having a coffee there, but it was the fact that it would be eventually transformed in to a giraffe house after the café was proven to be unnecessary.

As a lifelong Socialist, Cedric Price was a firm believer in architecture as an instrument of social improvement and of an architect as an ethical mediator or social engineer. On certain occasions, he would prefer to advise his clients to do nothing. In one of his conversations with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Price claimed that sometimes the best technical advice to the client might be, instead of building a house, to suggest a divorce. Photo courtesy of Kresimir Rogina.

In the same manner, the architectural proposal for Diego Garcia is thought to fully subordinate the needs of the coral. Therefore, the intervention would act as a trigger to regenerate new coral colonies, with its role and materiality ending once the colonies are established. Different nodes of the intervention are envisioned to be gradually placed over the lagoon’s most endangered areas. Each nod would consist of two parts. Firstly, the easily assembled structure below the water, that reinterpretates Buckminster Fuller’s tensegrity domes, and acts as a massive coral nursery where, through existing principles of coral farming, the endangered parts of coral on the lagoon’s seabed would be replanted inside the protected environment of the structural enclosure. Secondly, the buildings would gradually dock around the main circular structure serving as training centers for the local community and as research platforms for the Chagos Conservation Trust and other international parties that take place in current global environmental conversation. Both the underwater elements and the floating platforms are designed for a limited lifespan and once the coral takes over the main circular structure they will undergo a stage of corrosion ready to facilitate further spreading of the coral inside and around the buildings. As each platform is strategically located above one of the military anchoring points, while rejuvenating the corals, this environmental occupation could also progressively reduce the US military anchoring area in the island’s lagoon and gradually reclaim the full territory of the island. This architectural response attempts to make us rethink the fragility of the coral both as a weaponry and a line of defence and to challenge the defeatist assumptions that a small exiled community always has to bend to the will of powerful governments.

The architect has the power to link people, institutions, political and economic powers. In the expanded field of architecture, one continuously engages with questions of culture, political matters and human rights, offering a different perspective on understanding politics. Architecture cannot replace parliamentary governance, but precisely, its critical distance from conventional political bodies allows us to rethink architecture as a political instrument. While being an activist, one can delay, obstruct or prevent the process of demolition by physically blocking the threatened area but most likely will not offer the developer an alternative solution. Unlike other forms of activism such as art, journalism or public protest, architecture operates at a much slower and lasting pace. With the ability to directly impact the way we consume our cities, an architect has the ability to articulate an activist idea into a material and political reality.

- Featured Image: Jordi Colomer (Spain, 1962) Bucarest, 3´(2003) Video & projection, courtesy of the artist ↩

- ‘Architecture and Activism‘ Design Studio booklet by Torange Khonsari, Andreas Lang and Francesco Sebregondi (Royal College of Art, London, 2015), p.8 ↩

- For a history of the Chagossians legal battles see: Bowcott, O., Jones, S., UN ruling raises hope of return for exiled Chagos islanders, The Guardian, 19 March 2015], [Doward, J., Chagos Islanders’ fate to be decided by top court, The Guardian, 26 June 2016], [Bowcott, O., Chagos Islanders lose supreme court bid to return to homeland, The Guardian, 29 June 2016 ↩

- More: Langdon Winner, ‘Do Artifacts Have Politics?’, Daedalus, Vol. 109 (1980), pp. 121-136 & ‘Every Form of Art Has a Political Dimension‘, Chantal Mouffe interviewed by Rosalyn Deutsche, Brandem W. Joseph, and Thomas Keenan, Grey Room 02, Winter 2001, pp. 98– 125 ↩

- Arata Isozaki, ‘Erasing Architecture into the system’, 1975 in Cedric Price, Re:CP (Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhauser 2003), p.191 ↩

- Cedric Price, Works II, Architectural Association (London: Architectural Association, 1984), p.92 ↩

- Reyner Banham, Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), p.19 ↩

- Further reading: Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider and Jeremy Till, Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture (2011) Routledge, and documentary ‘Rebel Architecture: “Guerilla architect”’ with Santiago Cirugeda, Al Jazeera. ↩

- Forensic Architecture, Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (2014), p.11 ↩

- ‘Rebel Architecture: “The Architecture of Violence”’ with Eyal Weizman, Al Jazeera ↩

- ‘HGM floats proposal for marine reserve covering the Chagos Archipelago (British Indian Ocean Territory)’, 2009, Wikileaks ↩

- ‘Eyal Weizman on understanding politics through architecture, settlements and refuseniks’ by Amelia Smith (2014) ↩

- Further reading: ‘Architecture After Revolution’ by Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal and – Rebel Architecture: ‘The architecture of violence’ documentary with Eyal Weizman, Al Jazeera. ↩