Brett Scott writes about the city — its dynamics full of ambiguity and interfaces that connect and disconnect us from the larger context and from each other.

I once lived in Coffee Bay, a 260 person village on the rural Wild Coast of South Africa. It had a horizon so vast you could almost glimpse the curvature of the earth. There was one computer with a dial-up modem, and it almost never worked.That was just before I moved to London, to work in the steel and concrete of the city’s colossal financial sector. In London, as in many cities, you cannot see the horizon. On the other hand, you are connected to a vast hallucinogenic web of broadband media; constantly. That is, of course, provided the electricity does not go out.

In London, the electricity does not tend to go out. In South Africa though, we experienced the ‘rolling blackouts’ of 2007.1 In the absence of electricity people would wander outside, sit on the front steps of their houses, talk with passers-by and watch the stars that were normally drowned out by the glare of the city. The speed slowed down. People suddenly realized how much they took for granted.

Stars and horizons

In their natural setting, stars and horizons serve to remind you of your context: you are on a giant rolling planet, suspended within an enormous galactic system. That is something that does not actually sit well with the implicit ideology of the city. Forget being on a planet. You are in London, a uniquely important place in a uniquely important time, a control tower from which to master destiny and the external elements. Indeed, in the city, horizons and stars are just the basis for kitsch inspirational quotes (‘look to the horizon, reach for the stars’), pasted on the cubicle walls of wannabe high-flying young urban professionals, representing abstract places you cannot really reach.

And herein lies a central tension in the modern global mega-city. It might be a dynamic hub of glamorous entertainment, high-stakes commerce and edgy artistic sophistication; but it is also an engine of alienation, distancing us from the reality of our context, the land where food is grown, the grounds from which fossil fuels and metals are dredged and the ecological systems that underpin it all. In the city you are divorced from that broader context and placed into a different one — an exciting one perhaps — but a disconnected one nevertheless.

The disturbing possibility therefore, is that urban elites — whether in London, Brussels, Tokyo, Mumbai or New York – wield the greatest political and cultural trendsetting power, and yet may retain the least knowledge of the actual basis of their own survival. Those who do understand such realities — such as copper mine workers in Peru, or oil workers in the Niger Delta – are politically marginalized, and frequently looked down upon as backward objects of pity or faces on charity aid brochures. Urbanization is not slowing down.

In the era of hyper-consuming global metropolises we are now faced with a critical question bearing deep consequences: How does one live in the city whilst somehow retaining a grip on ecological reality?

This essay does not quite answer this question, but it sets out a map of the conceptual and practical territories that need to be covered. This map has guided my techno-shamanic adventure into the mire of the city, taken as part of a collective called Wisdomhackers.2 In delving into city life and technology, I am somewhat departing from my normal writings focused on the financial sector; though the link is deep. The financial sector is, after all, intensely urban and technological. I have a suspicion that some of the roots of the financial crisis and broader economic crisis are inextricably linked to city life itself.

Decoding Urban Dynamics

Urban ambiguity

Cities are deeply ambiguous, even contradictory places. On the one hand, they can be exuberant crucibles of cosmopolitan culture, liberating one from oppressive social bonds and bigotries, leaving you free to join loose floating groups of like-minded people. If you are an ostracized gay person in rural Mpumalanga, or an aspiring tech entrepreneur in the Australian outback, or Billy Elliot3 in a coal-mining town, are you going to stick around? Hell no! You go to Johannesburg, Brisbane or the Royal Ballet School in London and you become a city dweller just like me.

If there is one thing that we know about cities, it is that they are veritable hives of technology and the physical host for the ghostly force of innovation. That is as true today as it was during the Middle Ages. When people from distant small villages needed to buy their church bells they travelled and bought them from specialist smiths in London. Cities host economies of agglomeration and small towns frequently have too few people to support the capital and labour requirements of high tech industries. A similar thing can be said about the opera. If there are not enough people to support a big specialist theatre group in the Australian outback, they would pursue one in Sydney. This makes cities engines of ‘progress’, if defined in terms of material and cultural output levels. They churn out new ideas, new music, new sub-cultures, new technology, new everything, all the time.

On the other hand, cities also churn out an extraordinary amount of nonsense. They crawl with superficial phonies, egotistic businessmen, aggressive drivers, chancers and purveyors of meaningless fads. Pampered high-life culture meets low-life crime. Blinkered positive-thinking optimism meshes with hard-edged cynicism. And all the time, giant piles of material and cultural waste are shuttled out of sight into landfills. Cities, too, have long had a reputation for inspiring self-serving individualistic decadence and moral corruption accompanied by a history of people lamenting these dynamics. From the Book of Revelation reviling the depravation of Babylon, to Rousseau scolding city dwellers ‘depraved by sloth, inactivity, [and] the love of pleasure’,4 to Utopian Socialists leaving to start intentional communities in the countryside, to Gauguin leaving for Tahiti. Even Micah White of Occupy Wall Street began berating the cadres of urban activists and moved to Nehalem to launch a rural revolution.5

Perhaps urban ambiguity is rooted in the fact that the same loose bonds that can unlock empowering forms of freedom can simultaneously create disempowering forms of disassociation. Take, for example, early proletarianization, whereby people disenfranchised from the land drifted into wage labour in cities. The loosening of rural bonds was associated with the emergence of the ‘free’ human labour market, the ability to voluntarily detach oneself from social — and ecological — ties, eerily similar to how a marketed product detaches from those who produce it. The open-minded and expansive search for self is always prone to being twisted into the service of corporate power, taking the commoditized shallow form of the fun-seeking consumer shopping for identity.

Illusions of access in a world of interfaces

Many things are indeed very shallow in a city. Consider a simple plug socket, a two-dimensional interface discreetly inset within the wall. Somewhere, elsewhere, natural gas from the North Sea is being burned in turbines to produce a generic, seemingly invisible form of all-purpose energy called electricity, which is channelled via the electrical grid and now waits innocently for me at the plug. The wall blocks the outside reality while the plug presents a new one. We might say our experience of energy begins at the plug. Everything that happened before this is blocked out. Most interfaces are like this. One part blocks you from something, while another part invites you into something else. In the city we’re faced with a myriad of such interfaces. Consider the supermarket. The typical supermarket aisle is a sanitized interface. It presents us with free-floating items for consumption whilst simultaneously blocking awareness of their prior production processes that happened elsewhere. It is a key institution of modern psychological disconnection, doubling as an exemplar of modern sophistication. And what about the ATM? It is an interface into the banking system, a machine of convenience replicating the role of a bank teller. They are often placed next to physical bank branches, giving the impression that the money coming out of the wall came from ‘inside’ the bank. And what about my debit card? Is the money in the plastic card or elsewhere?

But even the seemingly down-to-earth world of physical buildings frequently represents a kind of interface. For all the rhetoric of city freedom, the average person experiences the city as a zone of things that you can see but that you will never actually interact with, a collection of human and physical objects, many of them out of bounds. The streets might be free to all, but the buildings are a series of locks and gates, or rather, paywalls and abounding differential access. I can look at the two-dimensional frontage of the Ritz, but can I experience the three dimensional space beyond the facade? You can of course use wealth to unlock these paywalls. Wealth brings a kind of universal freedom of the city access card.6 Albeit, ironically, if you are very poor you may be so marginalized that you gain a different sort of freedom to use parts of the city that many people willfully shut themselves off from; the parallel world of trashcan alleys, shacks and derelict squats.

For the average person though, the city expresses itself as a kind of aspiration, things you maybe one day will get to do. This phenomenon applies to human relations too. In the city you are faced with a constant stream of people you will never meet. Sonder is a neologism from the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows,7 referring precisely to the realisation that every person that passes you by is living a life as intense as your own, but one that you will never have access to; to them you are probably just an extra in the background.

FOMO meets YOLO in the buzz of constant surveillance

The ironic consequence of this is that you are almost never alone in a city, but surrounded by people who often do not offer much in the way of sympathy either. This is part of that hard-edged, bittersweet symphony city vibe.8 Of course, the endless stream of people offer potential for interaction, a tantalizing potential for sex, fun, intellectual debate and experience. It culminates in the ever-present fear-of-missing-out (FOMO) complex, breathlessly (and tragically) set against the ticking time bomb of the you-only-live-once (YOLO) complex.

The sense of never being alone is part of the city buzz. It also doubles as an element of a peculiar urban surveillance complex, joining the interconnected web of visible policing, endless lights and, if you glance upwards, CCTV cameras, all meshed together to give the subconscious awareness of always potentially being on someone’s radar. There are ways to escape the surveillance complex and at any one moment in central London you will find people existing in pockets of unmonitored space, feeling the wild tinge of alone-ness in a toilet cubicle, in old elevators, behind pillars in underground parking lots and in back alleys. We intuitively know where to find these places. Just imagine where you would go if you were trying to find a place to urinate in the city, or to have sex or basically to do anything slightly illicit.

In control of freedom

But even in the toilet cubicle you are not entirely alone. There are always the attempts to use the physical space to communicate with you, drunken messages plastered on the walls, and then, of course, there is the advertisement on the back of the door. Just like old communist cities were dotted with socialist realist artworks depicting idealized visions of humanity working towards common goals, so the surrealist corporate propaganda urges you to act on the goal of becoming something slightly different to what you are, to give in to vague fears or aspirations.9

Advertising is part of an obvious ongoing attempt to influence thought, to control to some end but it tends to cloak it within the banner of either freedom or of security. Under the hedonistic exterior of the Calvin Klein billboard there is clearly some highly strung obsessive executive trying to orchestrate a well-oiled campaign. It is the same with the friendly pleas for civility on the London Underground, or the Mayor’s cycling campaign, or the health and safety warning signs or the traffic lights and rules. They are all reflective of perhaps the deepest ambiguity of a city, between freedom and control and between control and its confusingly similar echo; security.

The perception of power and control as security is a hallmark of ‘mainstream’ status quo. It constitutes what we can (loosely) call hegemony, in a way that powerful institutions appear to be reassuringly normal in popular consciousness.

The police represent security to those in the mainstream and control to those on the outside, just like the smiling faces of corporate executives appear respectably professional to some and as exploitative masks of manipulation to others.

There is a long standing tradition of critiquing adverts, corporate executives and police violence, isolating the exploitative strands found within the comfortable security. However, perhaps the most pervasive control complex of the city is the most subtle and it is taken very much for granted and it is almost invisible. If there is one thing that most social classes implicitly agree on, it is that wilderness is not allowed to flourish in the city. Technologies of control, such as concrete, have been developed to resist the chaotic wiles of weeds. There are pest removal companies and poisons to remove pockets of alternative life as they form and tree surgeons assassinating rogue branches that do not obey council rules. Carefully tended parks might be allowed, but wilderness; NO!

The echo-chamber of urban elitism

The silent bulwarks of concrete control tend to get forgotten or hidden amidst the loud buzz of urban creativity and it is in this contradictory setting that a covert cultural agreement emerges. It runs across the political spectrum and across national boundaries. It is the tacit agreement that the city is where everything important happens, where policies are made and where trends are set. It is wired into urban mentality and above all it finds expression in people who consider themselves global jet-setters and in our favourite technology, the internet. The internet, when taken in aggregate, does not reflect ‘the world’. It reflects the relentless content production of large global cities and the transnational aspirations of transnational urbanites. There are up to 3 billion Google search results for New York. How many searches for the entire country of Angola? Around 126 million.

Urbanites have long been criticized for having their feet off the ground; for lacking an earthy connection to the soil. The sheer scale of this potential disconnection has increased as the sources of distraction have become richer than ever, a commercial media complex interwoven ever more closely into experience, the mobile internet streaming data from urban trendsetters around the world, music videos from San Francisco and stock prices from Hong Kong. This is the distraction complex, pointed out in Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle,10 the basis of Jean Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality.11 You can live an entire life in this cultural echo-chamber surrounded by others doing the same. Base level awareness of things like soil and rain merely distract from more important upper level realities. Who cares about watersheds when we can discuss vinyl, technology and business?

So let us talk business: All business comes down to raw human labour (physical or intellectual), which is supported by agriculture and augmented by technology (made with materials extracted from the earth), fuelled by energy sources. This formula is captured in everything from large-scale construction of highways to the simple act of using a photocopier after lunch. Though pinnacle of city business is finance; the portal for amplifying and steering previously accumulated capital into businesses of the future. The headquarters of global financial institutions are profoundly urban and it is in this setting that professionals make daily decisions about financing destructive projects in far-away places. The disconnected mentality of the city feeds into disconnected notions of economic life. Forest destruction is reduced to a series of numeric cash flow projections in excel spreadsheets.

Challenge

Getting behind the interfaces

Imagine it is evening in the city. You close down the spreadsheet and pull on your suit jacket to head across town to a bar. You make a pit-stop in a shop to pick up a disassociated pack of cigarettes piped in from some unknown location all the while petroleum-powered cars blurring past. If you were, however, to look down the back alley you pass, or through the sewer grilles under your feet, or behind the billboards, you would see that there are strange piping systems, ventilation shafts, bundles of wires, mechanical pulleys, delivery docks, waste management systems, storage depots, dirt and grease compounds. The world of interfaces is kept illuminated and co-ordinated via a vast, elaborate network of manual workers who will undertake all the steps necessary to seamlessly deliver a glass of cider down on a table in a Shoreditch bar.

This is the back-end, the spaces behind the interfaces. These are the only spaces in a city like London that you will not find adverts. For some the back end is a zone of resistance. It is where the urban foxes live and where squatters make homes in old abandoned pubs. It is where community gardens are started and where graffiti artists practice their craft. It is where weeds grow untended as little outposts of ecological resistance against concrete control. There are wild tomatoes growing on the banks of the Thames, if you know where to look. It is also in this space that the urban exploration subculture emerges; explorers of abandoned buildings and places you are not supposed to see. The urban exploration crew is drawn to all that is designed to be out of bounds, which happens to include most key elements of city infrastructure, the underground train systems, telecommunications towers, electrical power yards, warehouse complexes, sewerage systems and the logistics nodes in the shadows or on the outskirts. They are back-end adventurers; on the one hand rebellious but perhaps also seeking solace in places that nobody expects to find you in. It is a strand of the underground tradition of psychogeography, the attempt to defy or redefine the hegemonic logic of city spaces.

Bringing the back end to the front end

The key of the challenge is to explore how these vast back end systems and the ecological systems that they are drawn upon, can be brought into awareness within the very space that hides them. There are already urban movements that attempt to do this. The urban agriculture movements, for example, try to bring farm life right into the physical space of the city, creating rooftop plantations and city farms. In a more rebellious vein, there are guerrilla gardeners seed-bombing the stilted rows of public parks and manicured gardens with reckless wildflowers.

But when trying to define what part new high technology can play in all this, we are faced with a dilemma: technology has historically been used to cushion us from external realities. The streaming media capabilities of smart-phones have the seemingly obvious potential to open our eyes to things, but they have also created an information bubble which appears on a day-to-day basis to mostly dull the senses, not bring them alive to unseen realities.

It is worth exploring different approaches to using such communications technology. Firstly, it is worth looking at abstraction techniques, technologies that take a complex external reality and attempt to make it into something understandable or present it in the form of an analogy. For example, think of big data visualisations of internet usage,12 or mapping projects transforming the global subsidiaries of Goldman Sachs into a digestible form. It is an approach that really attempts to compress the disorientating scale of modern life into bite-sized chunks.

Secondly, there are humanising techniques, ways of taking something that is currently abstracted or obscured and showing the story behind it. For example, can we build open data maps of supply chains and populate them with personal stories and data on resource usage?13 Perhaps even Google maps can be used: I have used StreetView to virtually drive the back streets of Hong Kong to get a glimpse of Shenzhen where my iPhone was assembled.

And then there is the mother of all abstract façades, the financial sector, entrenched behind a firewall of political power and technical obfuscation. How might we breach the slick shell of financial instruments to view the gritty real world beneath?

Is there a way to read the Financial Times that will bring attention to the deep human and ecological dynamics embedded in the cold financial abstractions?

Can we take a flat story about stock market regulation and see it for what it is; a network of urban politicians interacting with a network of urban businesspeople battling it out amidst cultural constructions of risk, debt and the perceived potential of ‘assets’ in far flung and probably marginalized production centres?

The battle for holistic fusion

Maybe none of this works without people being willing to adopt a certain critical orientation towards surface appearances. Groups like BankTrack14 do try to show the human and environmental stories behind major bank deals, but bringing those stories into the public domain is tough. How do you bring marginalized voices into the city, to the ears of people who implicitly benefit by remaining ignorant? It is a crucial battle for holistic fusion. Because the countryside and the city appear to me like the imagined split between body and mind, physicality and intellectuality, hard labour and innovation. Furthermore, in the same way that the artificial distinction between body and mind needs to be fought; the consciousness of the city needs to be fused with the consciousness of all those vast tracts of the earth’s surface that feed into it.

* A slightly different version of ‘Bringing the Jungle to the City’ was originally published at Contributoria

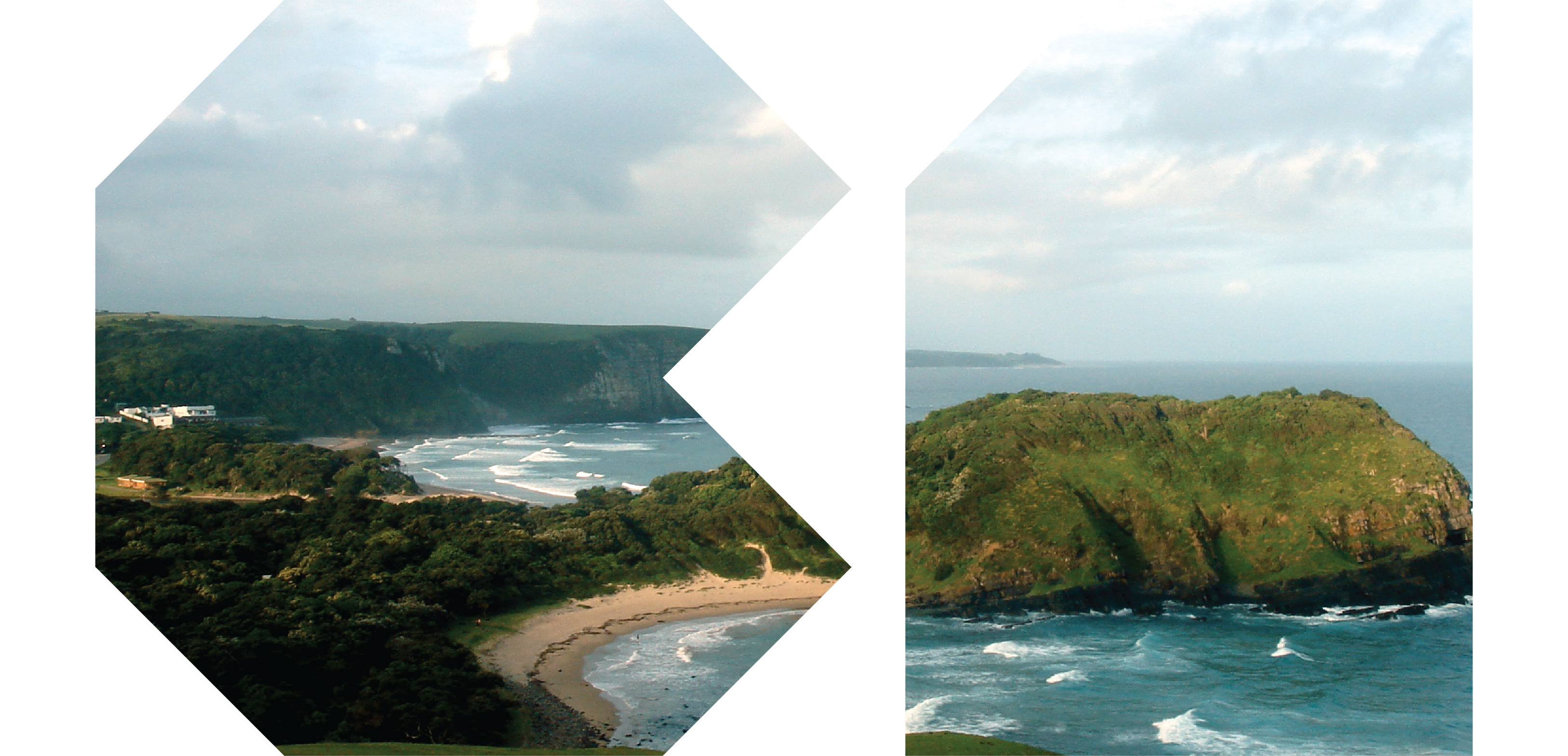

Feature Image: , Coffee Bay, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa.

- Rolling blackouts are controlled power shutdowns, engineered by utilities companies when they cannot match the demand. From October 2007, Eskom, South Africa’s main electricity supplier started implementing rolling blackouts throughout the country and by January 2008, it imposed a halt to major industries. ↩

- Wisdomhackers is a 26 person collective all immersively exploring different aspects of modern life. The collective includes Aina Abiodun, grappling with the implications of techno-utopianism, Anna Stothard, rethinking our relationship with physical objects in a throwaway consumer culture obsessed with change, Antoine Sakho, exploring technology consumption philosophy, Nathan Schneider, working on new social contracts, Lee-Sean Huang, exploring the disembodied experience of ‘knowledge work’, and Brock leMieux, experimenting with digital learning infrastructures and it is coordinated by the ‘Amish Futurist’ and explorer of informal pirate economies, Alexa Clay. ↩

- Billy Elliot (2000) Stephen Daldry [film], United Kingdom: BBC Films, Tiger Aspect Pictures, Studio Canal, Working Title Films ↩

- “The City” according to Rousseau, online ↩

- Amber Cortes (2014) An Occupy founder says the next revolution will be rural, Grist, online ↩

- Freedom of the City refers to a title of honorary citizenship awarded by cities to esteemed visiting celebrities and draws back to a medieval tradition of granting respected members of a community with freedom from selfdorm and special privileges in the city. ↩

- John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, online ↩

- The Verve (1997) Bitter Sweet Symphony [Music Video] United Kingdom: Hut Recordings The Verve lead singer Richard Ashcroft, walks down a busy pavement in Hoxton, North London, oblivious to what is going on around him, bumping into passers by and nearly getting hit by a car. Perhaps appropriately, the album where the song is featured is called Urban Hymns. ↩

- Minority Report (2002) Steven Spielberg [film] USA: Amblin Entertainment, Cruise/Wagner Productions, Blue Tulip Productions and Ronald Shusselt/ Gary Goldman Productions In this fragment of Minority Report, John Anderton (Tom Cruise) who has just undergone an eye transplant is navigating through a city overtaken by cameras and optical recognition systems, where he is bombarded with personal advertising of dystopian proportions. ↩

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (French: La Société du spectacle), (Paris: Buchet-Chastel, 1967) ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (French: Simulacres et Simulation), (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981) ↩

- The Internet Map is an interactive directory of about 350,000 websites, mapping their relative position in the world wide web. ↩

- A good example of this is Source Map, a company that provides visualizations of end-to-end supply chains, mapping where raw materials are produced, assembled and packaged and the people behind the supply chains. ↩

- BankTrack is a Netherlands-based foundation that follows the activities financed by commercial banks. Their goal is to promote transparency and accountability of such large financial organisations. ↩