An Old Way of Living, Yet Innovative

The Statement on the International Co-operative Identity ratified by the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) in 1995 voices that ‘Co-operatives are based on the values of self-sufficiency, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity’. Nearly 20 years later terms such as ‘self-sufficiency’ have acquired an extensive array of meanings, ranging from energy and food production to the advent of a myriad of types of user-generated multimedia content provided by the so-called web 2.0.

The Construction of a Community

It seems that in this context, dominated by mass production of large corporations, we are no longer able to find an adequate expression of the above-mentioned values.Perhaps that’s why we are observing a slow change in perspective towards the relationship between individuals and society and a transition from the large quantity-oriented production of goods dominated by a few companies, to a fragmented production of small quantities that, through a network of interactions, matching the quantities normally produced massively. Energy, food production and the Internet are particular examples of this transformation.

The attempts of co-housing initiatives and the so called ‘DIY Urbanism’, however still immature in Italy when compared to other countries such as Denmark, Sweden or the Netherlands, show how we could get closer to the idea of constructing the city from the ground up. In a way that would make space for individual initiatives, which can often produce more innovative models and promote a stronger sense of identity of the inhabited places because of the deep motivation of the people involved. Following these objectives the United Nations declared 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives. 2 [2] With the theme of ‘Co-operative Enterprises Build a Better World’, the International Year of Co-operatives 2012, seeks to encourage the growth and establishment of co-operatives all over the world. It also encourages individuals, communities and governments to recognize the agency of co-operatives in helping to achieve internationally agreed upon development goals, such as the Millennium Development Goals. http://social.un.org/coopsyear/ (accessed 20 December 2014)

Rochdale co-operative pioneers’ (1865)

The first co-operative in the world was created in 1844 in Rochdale, Great Britain, by a group of people who set up a self-help community to address economic problems, such as finding reasonably priced food.

Visit www.rochdalepioneersmuseum.coop for more information about Rochdale pioneers.

In a world in which consumption is defined by market rules instead of actual needs, we observe a more or less conscious return to the principles that inspired modern co-operatives born in the late Nineteenth century. The first co-operative in the world was created in 1844 in Rochdale, Great Britain, by a group of people who set up a self-help community to address economic problems, such as finding reasonably priced food. The power of acting cohesively allowed them to build a stronger stand in defining the relationship between production and consumption, as well as enabling them to help those who could not provide for themselves.

Housing co-operatives work according to similar principles, because they treat housing as one of the basic human needs. By doing so they provide an answer to the difficulties people face when applying for mortgages, to high rental costs and insufficient provision of accommodation that would respond to individual requirements.

Co-operatives are able to act as powerful interlocutors when dealing with the purchase of land, negotiating time and cost of construction that cater to the actual needs of their members.

At the same time they cancel the relationship between the developer and the client, because the community of the co-op becomes a client of itself.

A Journey to Italy: SEAO, a Co-operative in the City

SEAO, the first housing co-operative established in Italy, was founded in 1879 in the wake of the industrial revolution that for the first time brought the figure of the industrial worker to Northern Italy. SEAO was founded to build an economic and social capital, which would allow the construction of decent housing for its members.

The SEAO (the Società Edificatrice Abitazioni Operaie, literally The Building Association for Workers’ Housing) declares in its statute to take the responsibility not only for the pure construction, purchase, maintenance and management of the property given for use by members, but also for the facilities and services that could enhance their quality of living. They declare to cherish values that would provide for better social integration, cultural elevation and healthcare. The co-op focuses also on a broader scope of the needs of its inhabitants. It takes into account their extended relationships with the residential complex, urban area, as well as the local authorities and agencies that are involved in the management of the property including the available public services and facilities.

It is important to note that this statute was written in a time when there was no form of social security, and the young Italian state was struggling to face the unprecedented problem of provision of social housing for a large amount of industrial workers who migrated to the cities. In these circumstances private citizens (not only industrial workers, but also other employees and intellectuals) adopted this form of a ‘mutualistic sociality’ in which they helped each other for no profit. From the very beginning the initiative has been secular and not related to charity, which at the time of its foundation was very innovative. The initial members of the SEAO aimed to create a critical mass that would allow them to interact with institutions, public leaders, landowners and construction companies in order to provide themselves with decent and affordable houses. Now the SEAO has more than 1,300 members and manages around 400 houses and it is still one of the most well functioning housing co-operatives in Italy.

The criteria for membership has never been restricted by the level of income or the type of employment. Openness, flexibility and a pragmatic approach defined SEAO’s principles from its very beginning.

Moreover its founding ambition did not only focus on the pure provision of decent accommodation, but aimed to improve and enrich the living conditions of its members. For that reason the settlements until this day also include functions that are not strictly residential.

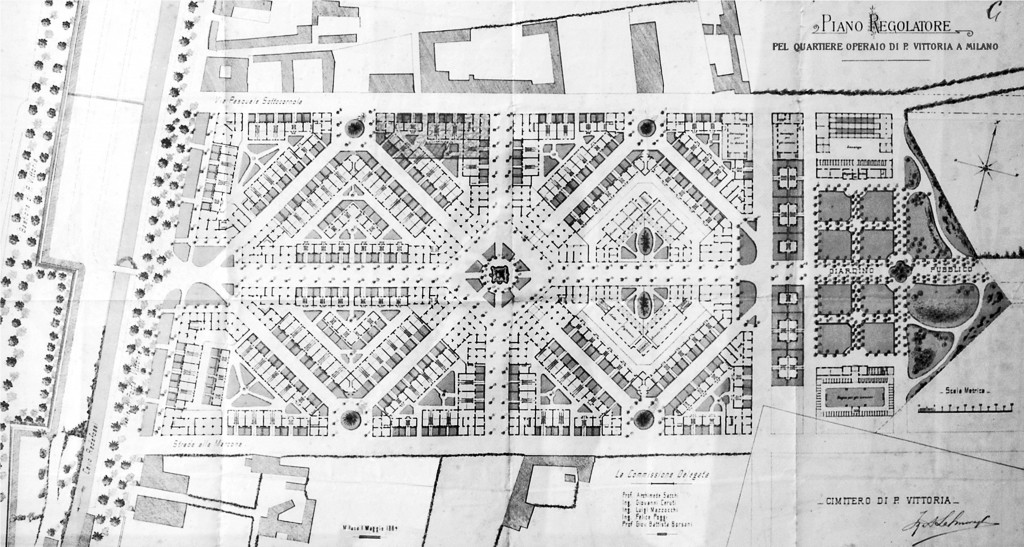

The first large-scale project the co-operative proposed was called the Ideal City. It was a development of rich complexity for a big urban area in the city centre of Milan. The plan included houses for sale and for rent with services such as dormitories, kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, recreational areas, shared laundries and storage.

The first large-scale project the SEAO co-operative proposed was called the Ideal City. It was a development of rich complexity for a big urban area in the city centre of Milan. The plan included houses for sale and for rent with services such as dormitories, kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, recreational areas, shared laundries and storage.

The settlement would be surrounded by a green area with small plots of private land for urban gardens. This green area was meant to recreate a strong relationship with the land, that was especially important to the people coming from the countryside, but also aimed to create a future minimal self-subsistence.

Few Rules Define Interesting Features

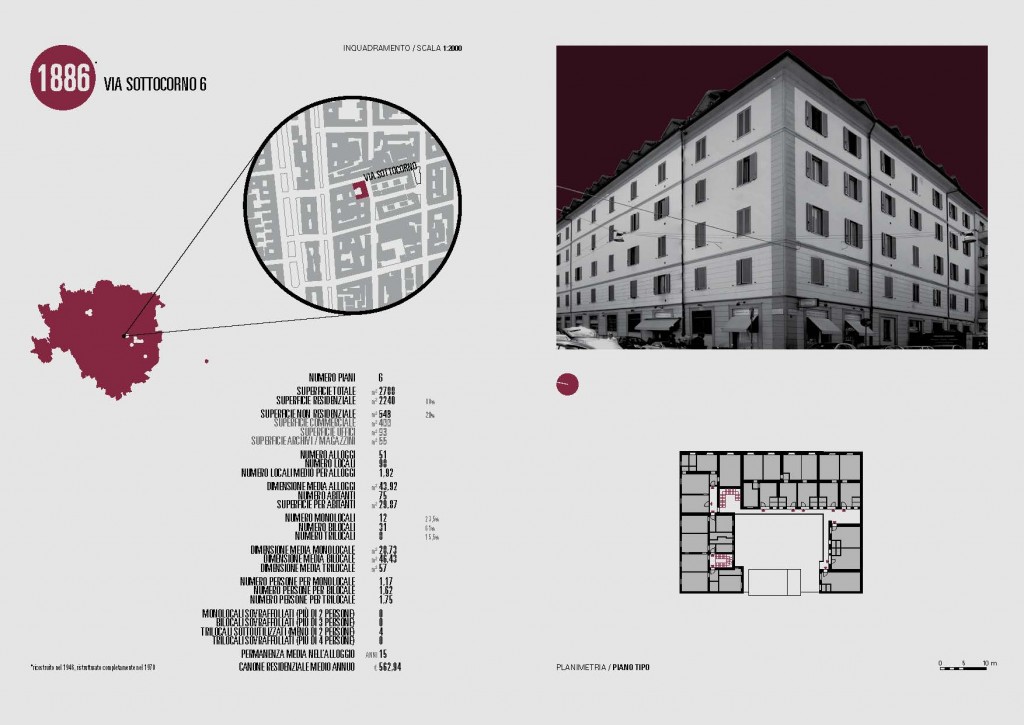

Eventually only a part of the Ideal City was realized and it still exists and functions today. Partial or not its realization was crucial to form one of the fundamental notions defining the co-operative: the transition from a divided property to the undivided property. 3 [3] In an undivided property co-operative, the ownership of the houses belongs to the co-operative: the members of the co-op have only a sort of usufruct for their houses. Statistic measures taken in 1895, after the construction indicated that only one third of the houses of the Ideal City were bought by the shareholders. Most of them were returned to the co-operative, resold (at a profit) or sublet. The significant failure of the sales owed to the low flexibility of the system to adapt to changes. Normally a long-term commitment, such as a mortgage, discourages the buyers from significant changes in the family unit. It affects its ability to quickly grow or shrink and precludes professional mobility that would involve displacement. At the same time it encourages maintenance of that same economic status as when signing the contract. Therefore in 1898 SEAO became a co-operative with undivided ownership where houses were made available through the payment of a canone di godimento (a fee for enjoying the house). It is a sort of rent that is affordable, unlimited in time and has no restrictions to the members’ income. The only rule is that the members cannot own a house in the metropolitan area of Milan. This is one of the aspects that differ co-operative housing from social housing in Italy.

With this rule the organization includes those who have a house in another part of Italy (or Europe) but work or study in Milan. It allows to create a good social mix in the community and to avoid ghettoization. Those who can afford to buy a house in Milan at a market price are not keen on joining the co-operative because not only would they have to join a long waiting list, but also because the houses have rather modest sizes (55 sqm on average). These conditions allow the system to self-regulate. Eventually the inhabitants create a mix of low to medium income families that come from different places and need a house in the city.

This aspect is really important when we realize how many problems of social housing come from the homogeneity of the social background of the inhabitants, that are mainly low-income families struggling to pay the rent and maintain their apartments properly. Creating a social and economical mix is beneficial to both the co-operative and the inhabitants and it is made possible by the flexibility and openness that the co-operative is based on.

It is also interesting that the members of the co-operative can inhabit their homes for an unlimited period of time. If a householder should die, the partner inherits the right to stay in the house. This also applies to homosexual relationships, which is rather progressive taken the fact that formally in Italy homosexual unions do not yet have legal rights.

It can be said that the commendable features of a co-operative housing association are its openness (anybody can subscribe), pragmatism (no ideology or lifestyle is required) and simplicity (simple guidelines, open to change and discussion).

Their long existence, which already exceeds 130 years, can serve as a confirmation of success and should be considered as a big achievement in an urban environment defined by constant change.

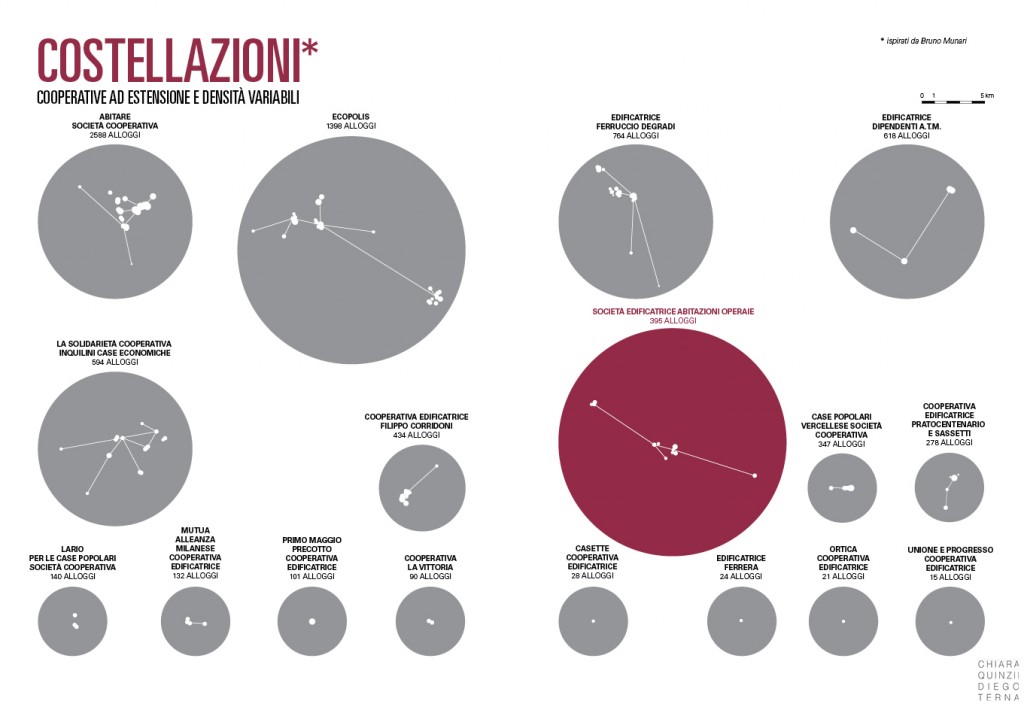

The Undivided Property, or about the Modification of the Entire City

Today within the municipal boundaries of Milan, there are a dozen of undivided property co-operatives with a real estate portfolio of approximately 8,000 houses. This corresponds to slightly more than 10 per cent of the public real estate assets.4 [4] Chiara Quinzii, Diego Terna, Ritorno all’abitare. Una cooperativa in città, 2012 It is a considerable share that can be an effective counterforce to the speculative building practices that have been dominating the growth of the city in recent years.

Current map of the real estate portfolio of undivided property co-operatives in Milan (it is about 8,000 houses, which corresponds to slightly more than 10 per cent of the public real estate assets).

The co-operatives can also be seen as an alternative to social housing, especially since its providers do not seem to have either the same financial resources nor a clear vision about how to preserve and invigorate the heritage they manage, which is in decline.

Not all Italian co-operatives are still actively constructing houses. Some of them are labelled as dormant because they do not build new houses and they tend to pass the use of the existing properties from one generation to another within the same family. This is in fact one of the biggest problems for associations of this kind, but the number of dormant co-operatives is quite small and the phenomenon is not growing. In SEAO 25 per cent of the members are related in some way: one of the reasons for this is that parents often subscribe their children with the co-operative when they are 18 years old, so they can be first on the list by the time they graduate, which can be read as only natural for a well working system.

Many of the undivided property co-operatives still exist, but because Italian housing policies are oriented towards the property market they do not manage to build a lot. In the last 10 years there was an average growth rate of 4 per cent in the property assets of the co-ops.5 [5] Chiara Quinzii, Diego Terna, Ritorno all’abitare. Una cooperativa in città, 2012 They focus more on the maintenance of the existing properties and improvement of the facilities they provide. The maintenance should not be underestimated because most of their dwellings were already built more than 60 years ago. Despite their age however, most of them remain in very good condition. Their standard is in that sense undistinguishable from the ones offered at market value. This is yet another difference between the co-ops and the social housing system that struggles to keep the houses in good condition while it offers them for roughly the same rental price. Does this reflect the better management or are the people living in co-operatives’ houses more respectful of their homes? It is possible that both reasons are true.

Today ABITARE focuses on the maintenance of the existing properties and improvement of the facilities they provide. Even though most of their dwellings were built more than 60 years ago they remain in very good condition.

Co-operatives meet the modern needs of living in the city and build communities that decide to live together not only for economic reasons but also for a higher quality of living through encounter, exchange and sharing.

This effort becomes even more significant if we realize that it operates in the rental sector which has much more stringent regulations than the sales sector. Perhaps the undivided property can provide a better answer to the urgent need for rental housing that meets the requirements of working flexibility and the contemporary patterns of changing family composition. It can respond to the needs of those who have to move to study, those unable to earn enough money for a purchase of a house or to ease the burden of being bound to a commitment as onerous as a home purchase.

The indivisibility of resources and their management introduces important values to the contemporary urban condition. The built environment is a part of the heritage not only for those who enjoy it directly but also for the future generations. The undivided property co-operatives play the role of land managers in vast parts of the city leaving the property undivided and manageable over the long term. In that situation the area that can be affected by external changes in the direct urban surrounding is not reduced to one or a few apartments, but expands to the scale of a block or even a neighbourhood, which stimulates a dialogue with the city and becomes an example of an original sociality.

ABITARE, the biggest undivided property co-operative in Milan, could be an interesting example of a modern approach towards community development on a larger scale. It has 2,623 dwellings and 97 commercial spaces in over 22 neighbourhoods, but most of its houses are concentrated in one area of the city. Because the blocks are concentrated in a specific area they tend to operate very well at the scale of the neighbourhood, which is different from the houses of the SEAO, for example, that are fewer but more scattered around the city.

ABITARE, the biggest undivided property co-operative in Milan, has 2,623 dwellings and 97 commercial spaces in over 22 neighbourhoods, but most of its houses are concentrated in one area of the city.

As a result of an internal investigation the organization of ABITARE realized that nowadays the creation of a community was no longer driven by an ideology or a unity related to the same profession (like it was historically created by the workers of the big industry). In response to that they decided to offer a great amount of collective services besides accommodation, so they reanimated their historical theatre and a library. The facilities are public and offer high quality shows that attract people from the entire metropolitan area of Milan. The co-op also offers social and healthcare facilities (especially for old and/or handicapped people) as well as sport and cultural facilities. All are open to the city and there are no exclusive memberships, which helps to create a new social mix, a wide exchange and keeps the services at a fair price.

Could housing co-operatives start to take care of the public space between their buildings in the future? Can their potential growth trigger a dialogue with urban polices? Are they an old and well-tested way of urban living that is still attractive today? The answers to these questions should become the agenda of tomorrow for the undivided property co-operatives and the cities.

* The text is based on the book by Chiara Quinzii and Diego Terna titled ‘Ritorno all’abitare. Una cooperativa in città’ (Back to Housing. A Co-operative in the City). The book was designed by Davide Rapp and published by LetteraVentidue Edizioni in 2012. It is available in an Italian language version. English speakers can find additional information on the book and the related research at http://ritornoallabitare.tumblr.com/.

comments [0]